Over the last decades, we have learned a great deal about the ways in which class inequalities profoundly overlap with race in Latin America. In most countries in the region, Latin Americans of more notable African and indigenous descent fare worse than the rest of the nation on nearly every socio-economic measure including income, education, and health. 1 They also have an abysmal share of their countries’ political and economic power. 2 In Brazil, where the most consistent and robust data on ethno-racial disparities exists, we also know that non-white Brazilians are more likely to be incarcerated and murdered by the police. 3 These inequalities are undeniably linked to Latin America’s legacy of colonialism and slavery, as well as the more generalized barriers to social mobility in these countries. Increasingly, studies on the region have likewise found that the persistence of ethno-racial inequality is also the reflection of ongoing practices of ethno-racial discrimination. 4

Yet, until very recently, state officials in Latin America had argued that the prevalence of race mixture, a tradition of colorblind legalism, and the lack of Jim-Crow-like laws restricting citizenship by race had effectively eliminated these countries’ racial problem. A Colombian diplomat captured this idea well in a 1984 report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD): “The legal and social organization of Colombia has always guaranteed racial equality and the absence of discrimination [against] any element of the population.” Similarly, in 1978, a Brazilian diplomat stated in a UN meeting that “even though there is a multiplicity of races that live within our borders, racial problems simply do not exist in Brazil.” 5

State discourse changed dramatically beginning in the late 1980s, however, when Latin American governments ushered in a new wave of multicultural and antiracist reforms, evident in the shift in state discourse, legislation, and constitutional reform. While there had been a great deal of scholarly focus on the inclusion of indigenous rights in these new constitutions, much less attention had been paid to the arguably more surprising shift to recognize the rights of the region’s Afro-descendant populations. In 1986, Nicaragua became the first country to recognize the collective rights of black communities alongside the recognition of indigenous communities’ rights. Over the next decade, a handful of other countries would follow, among them Brazil (1988), which included land rights and cultural rights for quilombolas (escaped slave communities) in its reformed constitution, and Colombia (1991), which recognized the rights of black communities on the country’s Pacific Coast.

Along with this recognition came a plethora of unprecedented rights and policies relating to such issues as collective landholding, natural resources, alternative development, mandatory inclusion of black history in educational curricula, recognition of national holidays celebrating black history and culture, and more. In some countries, these changes also included the criminalization of racism, as well as affirmative action policies in universities, government jobs, and even in political office. Beyond recognizing the existence of populations of African descent, these laws institutionalized a collective legal subject that acknowledged the unique histories and experiences of people of African descent. These important symbolic victories also had material implications. In Colombia, ethno-racial rights led to the largest agrarian reform in that country’s history, and today, about a third of Colombia’s national territory is under collective title to indigenous or black communities. In Brazil, affirmative action in public education radically transformed the student bodies of the country’s most prestigious universities in terms of color and social class. Perhaps because of these high stakes, the last decade has also been characterized by the rise of reactionary movements created to undermine ethno-racial rights.

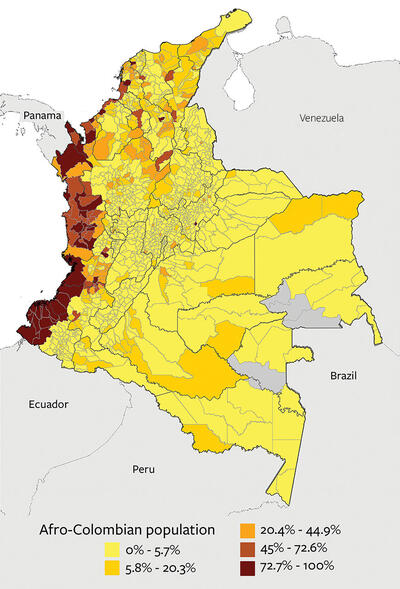

The adoption of specific policies for black populations in Colombia and Brazil was not simply a policy change; it amounted instead to a dramatic change in discourse of state institutions, as well as a transformation of the way that citizenship was defined in these countries. Nevertheless, it did not naturally follow that these political changes would actually matter in the lives of ordinary people in these countries. In both Colombia and Brazil, ethno-racial legislation had inherent limitations. There was also the notorious gap between laws on paper and actual state practices. In keeping with the popular Brazilian adage, “there are laws that stick and laws that don’t,” and the Colombian saying, “there are more laws than people,” the ability of legislation to transform daily life in these countries is viewed with widespread skepticism. All this begs the question: To what extent has the adoption of specific policies for black populations translated into real change on the ground?In my book, Becoming Black Political Subjects, I examine the causes and consequences of Latin America’s turn to ethno-racial rights, focusing specifically on black populations and on the cases of Brazil and Colombia. Those countries stand out as central examples within the region, not only because of the size of their Afro-descendant populations — first and second in Latin America, respectively — but also because they were among the earliest cases of black rights and adopted the most robust legislation. One of the main questions I ask in the book is: Why did the Colombian and Brazilian states go from citizenship regimes based on ideas of the universal and formally unmarked citizen to the recognition of black rights? I argue that in both cases, they did so in the face of pressure from black social movement organizations. However, while these movements were essential to the making of black political subjects, they were actually small and under-resourced networks of activists. Activists who also had very few political allies and were unpopular with, and largely unknown to, the masses. In fact, social movement scholars might debate the extent to which they were “movements” at all. Even so, the story I weave together here is still fundamentally about how black social movements in Colombia and Brazil did succeed — against all odds — in bringing about specific legislation for black populations, as well as substantive changes in popular discourse. In addition to analyzing the strategies they used to achieve these ends, I also examine how their embeddedness in a complex field of local and global politics often blurred the very definition of social movement.

In both cases, the implementation of ethno-racial legislation has depended heavily on the ways in which activists navigate their domestic political fields, including how they negotiate their newly gained access to the state. It is also profoundly shaped by the emergence of reactionary movements. Indeed, as the dominant classes became increasingly aware of what was at stake with these rights and policies — land, natural resources, seats in congress, and university slots that could maintain or secure one’s place within the middle class — they sought to dismantle them, sometimes through violent means. In both Colombia and Brazil, these dynamics of institutionalization and backlash are important to understanding the partial unmaking of black rights, in which black movement gains of the last few decades have remained on paper, were restricted, or were undermined entirely.

Colombia’s Law 70, or the Law of Black Communities (1993), has five substantive chapters, each focusing on a specific area: land; natural resources; ethnic education; mining; and social/economic development, each to be implemented through separate pieces of legislation. Yet, despite 20 years of promises by Colombian presidents, ministers, and directors of the Office on Black Communities, the chapters on ethno-education and territory were the only ones that had been implemented. Even in those areas, there were still serious limitations, including the fact that less than 10 percent of Colombia’s public schools had adopted the legally mandated curriculum on Afro-Colombian history and culture. 6 In this sense, a number of key provisions in this legislation can be said to be letra muerta (dead law). The only silver lining has been Colombia’s record on land titling of rural black communities, which is impressive, especially when compared with Brazil, where efforts to recognize collective titles have largely been crippled. Even so, just as black communities were gaining collective titles, they found themselves having to respond to increased violence, illegal mining, environmental degradation, and forced displacement on those same lands.

In Brazil, the challenges around ensuring the exercise of newly gained rights and the implementation of ethno-racial policies were similar, though somewhat distinct. The biggest failure of Brazil’s ethno-racial policies has been the titling of quilombo land. To date, only one million hectares (less than 2.5 million acres) of land have been titled to quilombo communities. To put this number in perspective, this land is only a fifth of the amount that the Colombian state has titled to black communities, despite Brazil’s much larger size, greater number of officially recognized quilombos, and greater state capacity. The degree of quilombo titling reflects ongoing debates within the Brazilian state over what a quilombo community actually is. 7 Are they only communities that are the direct, and provable, descendants of runaway slaves? If former slave owners gave over their property to these communities, did the communities have to know this history? Did quilombos have to maintain cultural traditions to qualify for land rights? Just as in Colombia, the contestation over quilombo rights was also intrinsically linked to economic interest in this land.

In the wake of what were inevitably partial victories, what developed were entangled relationships between black movement actors and the state, as well as contentious debates within these movements over questions of authenticity, representation, and political autonomy. As many of the black activists who helped to bring about these important policy changes in these two countries spent the last decades fighting against state retrenchment, still others questioned the profound limitations embedded in Latin American states’ new ethno-racial policies.

One such organization is Brazil’s Campanha Reaja ou Será Morto/Morta (React or Die Campaign), a network of community-based organizations that emerged to politicize the deaths of black people and to expose police brutality and inequality in Brazil’s criminal justice system. While the organization began in 2005 in Salvador, it gained national and international media attention about a decade later with a number of marches against the genocide of black people. While the trend within the larger black movement had been working within state bureaucracies, Reaja was amassing thousands of protestors — first in Salvador and, later, in cities across the nation — who joined in marches against the extermination of black people. 8 While racism in policing had been a historic banner of Brazil’s black movement, it was one of several central demands that never quite made it to the state’s agenda around ethno-racial inclusion.

These limitations have only been exacerbated in the current moment of profound economic and political change. Just as Brazil was impeaching Dilma Rousseff, the country’s first female president and member of the Workers’ Party, Colombia prepared for an unprecedented peace agreement to end more than 50 years of internal conflict with the FARC. While Afro-Colombian activists effectively organized to include an ethnic chapter in the original peace accord signed in September 2016, their participation in the process deteriorated after Colombian voters voted “No” by a narrow margin in a national referendum. While a revised peace accord was eventually signed into law through congress, many of the agreements around Afro-Colombians and indigenous peoples’ participation have yet to be honored.

In Brazil, the highly politicized ouster of a Workers’ Party president whose platform included expanded racial equality policies and the subsequent downsizing and elimination of racial equality administrations within the federal government signals an end to the brief period of ethno-racial reforms in that country. In both cases, the parties that have led the movements against the expansion of social policy and further democratization have also led legislative efforts to get rid of ethno-racial legislation, including policies against collective ethnic land rights in Colombia and affirmative action in Brazil. All these political shifts and reconfigurations have direct implications on the future of ethno-racial rights and policies.

Throughout Latin America, countries have been experiencing the end of the so-called “pink tide” of democratically elected leftist administrations. It was under these administrations that many countries in the region saw unprecedented expansions in social welfare policies and reductions of economic inequality. This end of leftist regimes — which only sometimes has happened through natural electoral cycles — has also come amid a global commodities bust that has led to the worst recession in decades. These are precisely the kinds of moments of political and economic transformations in Latin America that are all too often told as colorblind stories where the racial dimensions and implications of these shifts are downplayed or ignored. Though, as Latin American countries brace themselves for these transformations, it is important to remember the region’s ongoing struggles to meaningfully incorporate its most marginalized citizens, some of whom have quite literally been erased from the nation. Indeed, much like the previous period of constitutional reform decades earlier, this moment raises serious questions about the extent to which Latin American states can ever really deliver on the promise to build inclusive democracies, especially in moments of crisis.

Tianna Paschel is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies at UC Berkeley. She is the author of Becoming Black Political Subjects: Movements and Ethno-Racial Rights in Colombia and Brazil (Princeton University Press, 2016). She spoke for CLAS on September 21, 2016.

References

1. See Gillette H. Hall and Harry Anthony Patrinos, Indigenous peoples, poverty, and development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2012), and Edward E. Telles, Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

2. Mala Htun, "Inclusion Without Representation: Gender Quotas and Ethnic Reservations in Latin America" (unpublished ms 2014).

3. See Christen A. Smith, Afro-Paradise: Blackness, Violence, and Performance in Brazil (Champaign: IL: University of Illinois Press, 2016).

4. See Edward Telles, Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America (Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press Books, 2014).

5. Brazilian diplomat, Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, 1978.

6. Figure taken from a report issued by Colombia’s National Council of Planning entitled Reflexión para la Planeación Balance General del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2006–2010.

7. See Jan Hoffman French, Legalizing Identities: Becoming Black or Indian in Brazil’s Northeast (Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 2009).

8. Smith (2016) offers a thorough analysis of the Campanha Reaja movement, including an examination of marches against the extermination of black people that drew thousands of people throughout Brazil.