The year 1932 was not a good time to come to Detroit, Michigan. The Great Depression cast dark clouds over the city. Scores of factories had ground to a halt, hungry people stood in breadlines, and unemployed autoworkers were selling apples on street corners to survive. In late April that year, against this grim backdrop, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo stepped off a train at the cavernous Michigan Central depot near the heart of the Motor City. They were on their way to the new Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), a symbol of the cultural ascendancy of the city and its turbo-charged prosperity in better times. The next 11 months in Detroit would take them both to dazzling artistic heights and transform them personally in far-reaching, at times traumatic, ways.

I subtitle this article “a history and a personal journey.” The history looks at the social context of Diego and Frida’s defining time in the city and the art they created; the personal journey explores my own relationship to Detroit and the murals Rivera painted there. I was born and raised in the city, listening to the sounds of its bustling streets, coming of age in its diverse neighborhoods, growing up with the driving beat of its music, and living in the shadows of its factories. Detroit was a labor town with a culture of social justice and civil rights, which on occasion clashed with sharp racism and powerful corporations that defined the age. In my early twenties, I served a four-year apprenticeship to become a machine repair machinist in a sprawling multistory General Motors auto factory at Clark Street and Michigan Avenue that machined mammoth seven-liter V8 engines, stamped auto body parts on giant presses, and assembled gleaming Cadillacs on fast-moving assembly lines. At the time, the plant employed some 10,000 workers who reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of the city, as well as its tensions. The factory was located about a 20-minute walk from where Diego and Frida got off the train decades earlier but was a world away from the downtown skyscrapers and the city’s cultural center.

I grew up with Rivera’s murals, and they have run through every stage of my life. I’ve been gone from the city for many years now, but an important part of both Detroit and the murals have remained with me, and I suspect they always will. I return to Detroit frequently, and no matter how busy the trip, I have almost always found time for the murals.

In Detroit, Rivera looked outwards, seeking to capture the soul of the city, the intense dynamism of the auto industry, and the dignity of the workers who made it run. He would later say that these murals were his finest work. In contrast, Kahlo looked inward, developing a haunting new artistic direction. The small paintings and drawings she created in Detroit pull the viewer into a strange and provocative universe. She denied being a Surrealist, but when André Breton, a founder of the movement, met her in Mexico, he compared her work to a “ribbon around a bomb” that detonated unparalleled artistic freedom (Hellman & Ross, 1938).

Rivera, at the height of his fame, embraced Detroit and was exhilarated by the rhythms and power of its factories (I must admit these many years later I can relate to that response). He was fascinated by workers toiling on assembly lines and coal-fired blast furnaces pouring molten metal around the clock. He felt this industrial base had the potential to create material abundance and lay the foundation for a better world. Sixty percent of the world’s automobiles were built in Michigan at that time, and Detroit also boasted other state-of-the-art industry, from the world’s largest stove and furnace factory to the main research laboratories for a global pharmaceutical company.

“Detroit has many uncommon aspects,” a Michigan guidebook produced by the Federal Writers Project pointed out, “the staring rows of ghostly blue factory windows at night; the tired faces of auto workers lighted up by simultaneous flares of match light at the end of the evening shift; and the long, double-decker trucks carrying auto bodies and chassis” (WPA, 1941:234). This project produced guidebooks for every state in the nation and was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal Agency that sought to create jobs for the unemployed, including writers and artists. I suspect Rivera would have embraced the approach, perhaps even painted it, had it then existed.

Detroit was a rough-hewn town that lacked the glitter and sophistication of New York or the charm of San Francisco, yet Rivera was inspired by what he saw. In his “Detroit Industry” murals on the soaring inner walls of a large courtyard in the center of the DIA, Rivera portrayed the iconic Ford Rouge plant, the world’s largest and most advanced factory at the time. “[These] frescoes are probably as close as this country gets to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote eight decades later (Smith, 2015).

The city did not speak to Kahlo in the same way. She tolerated Detroit — sometimes barely, other times with more enthusiasm — rather than embracing it. Kahlo was largely unknown when she came to Detroit and felt somewhat isolated and disconnected there. She painted and drew, explored the city’s streets, and watched films — she liked Chaplin’s comedies in particular — in the movie theaters near the center of the city, but she admitted “the industrial part of Detroit is really the most interesting side” (Coronel, 2015:138).

During a personally traumatic year — she had a miscarriage that went seriously awry in Detroit, and her mother died in Mexico City — she looked deeply into herself and painted searing, introspective works on small canvases. In Detroit, she emerged as the Frida Kahlo who is recognized and revered throughout the world today. While Vogue still identified her as “Madame Diego Rivera” during her first New York exhibition in 1938, the New York Times commented that “no woman in art history commands her popular acclaim” in a 2019 article (Hellman & Ross, 1938; Farago, 2019).

My emphasis will be on Rivera and the “Detroit Industry” murals, but Kahlo’s own work, unheralded at the time, has profoundly resonated with new audiences since. While in Detroit, they both inspired, supported, influenced, and needed each other.

Prelude

Diego and Frida married in Mexico on August 21, 1929. He was 43, and she was 22 — although their maturity, in her view, was inverse to their age. Their love was passionate and tumultuous from the beginning. “I suffered two accidents in my life,” she later wrote, “one in which a streetcar knocked me down … the other accident is Diego” (Rosenthal, 2015:96).

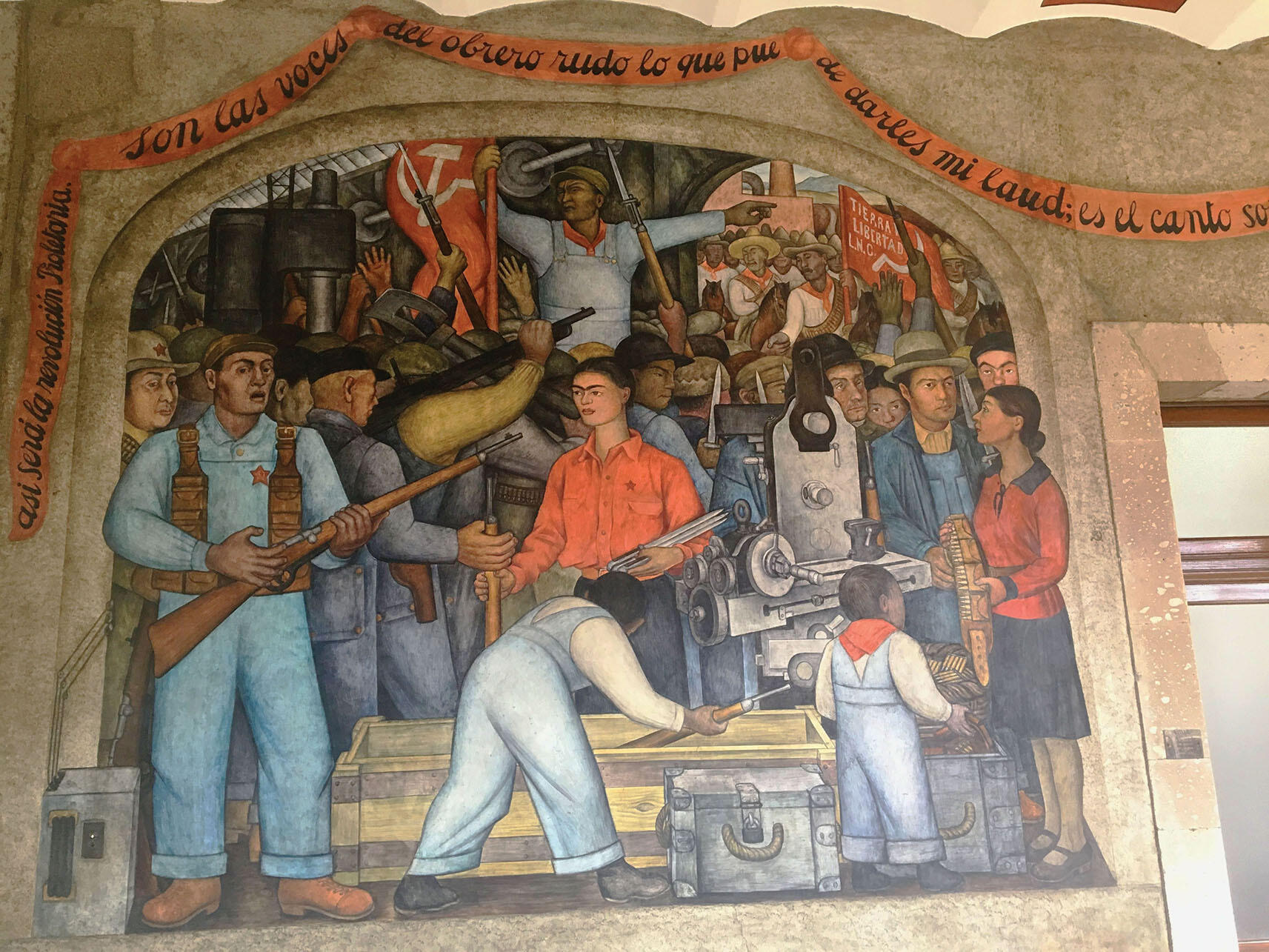

They shared a passion for Mexico, particularly the country’s indigenous roots, and a deep commitment to politics, looking to the ideals of communism in a turbulent and increasingly dangerous world (Rosenthal, 2015:19). Rivera painted a major set of murals — 235 panels — in the Ministry of Education in Mexico City between 1923 and 1928. When he signed each panel, he included a small red hammer and sickle to underscore his political allegiance. Among the later panels was “In the Arsenal,” which included images of Frida Kahlo handing out weapons, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in a hat with a red star, and Italian photographer Tina Modotti holding a bandolier.

The politics of Rivera and Kahlo ran deep but didn’t exactly follow a straight line. Kahlo herself remarked that Rivera “never worried about embracing contradictions” (Rosenthal, 2015:55). In fact, he seemed to embody F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notion that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” (Fitzgerald, 1936).

Their art, however, ultimately defined who they were and usually came out on top when in conflict with their politics. When the Mexican Communist Party was sharply at odds with the Mexican government in the late 1920s, Rivera, then a Party member, nonetheless accepted a major government commission to paint murals in public buildings. The Party promptly expelled him for this act, among other transgressions (Rosenthal, 2015:32).

iego and Frida came to San Francisco in November 1930 after Rivera received a commission to paint a mural in what was then the San Francisco Stock Exchange. He had already spent more than a decade in Europe and another nine months in the Soviet Union in 1927. In contrast, this was Kahlo’s first trip outside Mexico. The physical setting in San Francisco, then as now, was stunning — steep hills at the end of a peninsula between the Pacific and the Bay — and they were intrigued and elated just to be there. The city had a bohemian spirit and a working-class grit. Artists and writers could mingle with longshoremen in bars and cafes as ships from around the world unloaded at the bustling piers. At the time, California was in the midst of an “enormous vogue of things Mexican,” and the couple was at the center of this mania (Rosenthal, 2015:32). They were much in demand at seemingly endless “parties, dinners, and receptions” during their seven-month stay (Rosenthal, 2015:36). A contradiction with their political views? Not really. Rivera felt he was infiltrating the heart of capitalism with more radical ideas.

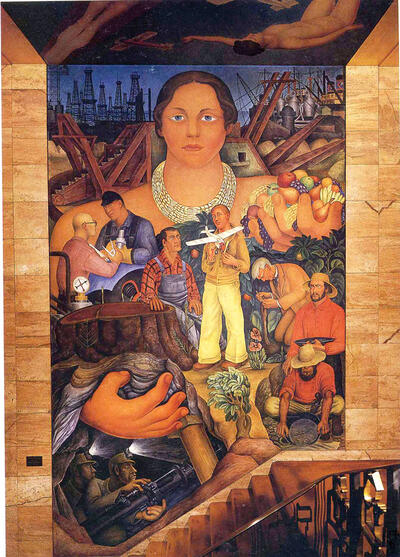

Rivera’s commission produced a fresco on the walls of the Pacific Stock Exchange, “Allegory of California” (1931), a paean to the economic dynamism of the state despite the dark economic clouds already descending. Rivera would then paint several additional commissions in San Francisco before leaving. While compelling, these murals lacked the power and political edge of his earlier work in Mexico or the extraordinary genius of what was to come in Detroit.

While in San Francisco, Rivera and Kahlo met Helen Wills Moody, a 27-year-old world-class tennis player, who became the central model for the Allegory mural. She moved in rarified social and artistic circles, and as 1930 drew to a close, she introduced the couple to Wilhelm Valentiner, the visionary director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), who had rushed to San Francisco to meet Rivera when he learned of the artist’s arrival.

When Valentiner and Rivera met, the economic fallout of the Depression was hammering both Detroit and its municipally funded art institute. The city was teetering at the edge of bankruptcy in 1932 and had slashed its contribution to the museum from $170,000 to $40,000, with another cut on the horizon. Despite this dismal economic terrain, Valentiner was able to arrange a commission for Rivera to paint two large-format frescoes in the Garden Court at the new museum building, which had opened in 1927. Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford and a major patron of the DIA, pledged $10,000 for the project — a truly princely sum at that moment — and would double his contribution as Rivera’s vision and the scale of the project expanded (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Edsel also played an unheralded role in support of the museum through the economic traumas to come.Valentiner was “a German scholar, a Rembrandt specialist, and a man with extraordinarily wide tastes,” according to Graham W.J. Beal, who himself revitalized the DIA as director in the 21st century. “Between 1920 and the early 1930s, with the help of Detroit’s personal wealth and city money, Valentiner transformed the DIA … into one of the half-dozen top art collections in the country,” a position the museum continues to hold today (Beal, 2010:34). The museum director and the artist shared an unusual kinship. “The revolutions in Germany and Mexico [had] radicalized [both],” wrote Linda Downs, a noted curator at the DIA (Downs, 2015:177). Little more than a decade later, “the idea of the mural commission reinvigorated them to create a highly charged monumental modern work that has contributed greatly to the identity of Detroit” (Downs, 2015:177).

A discussion of Rivera’s mural commission gets a bit ahead of our story, so let’s first look at Detroit’s explosive economic growth in the early years of the 20th century. This industrial transformation would provide the subject and the inspiration for Rivera’s frescoes.

The Motor City and the Great Depression

At the turn of the 20th century, Detroit “was a quiet, tree-shaded city, unobtrusively going about its business of brewing beer and making carriages and stoves” (WPA, 1941:231). Approaching 300,000 residents, Detroit was the 13th-largest city in the country (Martelle, 2012:71). A future of steady growth and easy prosperity seemed to beckon.

Instead, Henry Ford soon upended not only the city, but much of the world. He was hardly alone as an auto magnate in the area: Durant, Olds, the Fisher Brothers, and the Dodge Brothers, among others, were also in or around Detroit. Ford, however, would go beyond simply building a successful car company: he unleashed explosive growth in the auto industry, put the world on wheels, and became a global folk hero to many, yet some were more critical. The historian Joshua Freeman points out that “Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) depicts a dystopia of Fordism, a portrait of life A.F. — the years “Anno Ford,” measured from 1908, when the Model T was introduced — with Henry Ford the deity” (Freeman, 2018:147).

Ford combined three simple ideas and pursued them with razor-sharp, at times ruthless, intensity: the Model T, an affordable car for the masses; a moving assembly line that would jump-start productivity growth; and the $5 day for workers, double the prevailing wage in the industry. This combination of mass production and mass consumption — Fordism — allowed workers to buy the products they produced and laid the basis for a new manufacturing era. The automobile age was born.

The $5 day wasn’t altruism for Ford. The unrelenting pace and control of the assembly line was intense — often unbearable — even for workers who had grown up with back-breaking work: tilling the farm, mining coal, or tending machines in a factory. Annual turnover approached 400 percent at Ford’s Highland Park plant, and daily absenteeism was high. In response, Ford introduced the unprecedented new wage on January 12, 1914 (Martelle, 2012:74).

The press and his competitors denounced Ford — claiming this reckless move would bankrupt the industry — but the day the new rate began, 10,000 men arrived at the plant in the winter darkness before dawn. Despite the bitter cold, Ford security men aimed fire hoses to disperse the crowd. Covered in freezing water, the men nonetheless surged forward hoping to grasp an elusive better future for themselves and their families.

Here is where I enter the picture, so to speak. One of the relatively few who did get a job that chaotic day was Philip Chapman. He was a recent immigrant from Russia who had married a seamstress from Poland named Sophie, a spirited, beautiful young woman. They had met in the United States. He wound up working at Ford for 33 years — 22 of them at the Rouge plant — on the line and on machines. They were my grandparents.

By 1929, Detroit was the industrial capital of the world. It had jumped its place in line, becoming the fourth-largest city in the United States — trailing only New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — with 1.6 million people (Martelle, 2012:71). “Detroit needed young men and the young men came,” the WPA Michigan guidebook writers pointed out, and they emphasized the kaleidoscopic diversity of those who arrived: “More Poles than in the European city of Poznan, more Ukrainians than in the third city of the Ukraine, 75,000 Jews, 120,000 Negroes, 126,000 Germans, more Bulgarians, [Yugoslavians], and Maltese than anywhere else in the United States, and substantial numbers of Italians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Syrians, English, Scotch, Irish, Chinese, and Mexicans” (WPA, 1941:231). Detroit was third nationally in terms of the foreign-born, and the African American population had soared from 6,000 in 1910 to 120,000 in 1930 (WPA, 1941:108), part of a journey that would ultimately involve more than six million people moving from the segregated, more rural South to the industrial cities of the North (Trotter, 2019:78).

DIA planners projected that Detroit would become the second-largest U.S. city by 1935 and that it could surpass New York by the early 1950s. “Detroit grew as mining towns grow — fast, impulsive, and indifferent to the superficial niceties of life,” the Michigan Guidebook writers concluded (WPA, 1941:231).

The highway ahead seemed endless and bright. The city throbbed with industrial production, the streetcars and buses were filled with workers going to and from work at all hours, and the noise of stamping presses and forges could be heard through open windows in the hot summers. Cafes served dinner at 11 p.m. for workers getting off the afternoon shift and breakfast at 5 a.m. for those arriving for the day shift. Despite prohibition, you could get a drink just about any time. After all, only a river separated Detroit from Canada, where liquor was still legal.

Rivera’s biographer and friend Bertram Wolfe wrote of “the tempo, the streets, the noise, the movement, the labor, the dynamism, throbbing, crashing life of modern America” (Wolfe, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:65). The writers of the Michigan guidebook had a more down-to-earth view: “‘Doing the night spots’ consists mainly of making the rounds of beer gardens, burlesque shows, and all-night movie houses,” which tended to show rotating triple bills (WPA, 1941:232).

Henry Ford began constructing the colossal Rouge complex in 1917, which would employ more than 100,000 workers and spread over 1,000 acres by 1929. “It was, simply, the largest and most complicated factory ever built, an extraordinary testament to ingenuity, engineering, and human labor,” Joshua Freeman observed (Freeman, 2018:144). The historian Lindy Biggs accurately described the complex as “more like an industrial city than a factory” (Biggs, as cited in Freeman, 2018:144).

The Rouge was a marvel of vertical integration, making much of the car on site. Giant Ford-owned freighters would transport iron ore and limestone from Minnesota and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula down through the Great Lakes, along the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers, and then across the Rouge River to the docks of the plant. Seemingly endless trains would bring coal from West Virginia and Ohio to the plant. Coke ovens, blast furnaces, and open hearths produced iron and steel; rolling mills converted the steel ingots into long, thin sheets for body parts; foundries molded iron into engine blocks that were then precision machined; enormous stamping presses formed sheets of steel into fenders, hoods, and doors; and thousands of other parts were machined, extruded, forged, and assembled. Finished cars drove off the assembly line a little more than a day after the raw materials had arrived at the docks.

In 1928, Vanity Fair heralded the Rouge as “the most significant public monument in America, throwing its shadow across the land probably more widely and more intimately than the United States Senate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Statue of Liberty.... In a landscape where size, quantity, and speed are the cardinal virtues, it is natural that the largest factory turning out the most cars in the least time should come to have the quality of America’s Mecca, toward which the pious journey for prayer” (Jacob, as cited in Lichtenstein, 1995:13). My grandfather, I suspect, had a more prosaic goal: he needed a job, and Ford paid well.

Despite tough conditions in the plant, workers were proud to work at “Ford’s,” as people in Detroit tended to refer to the company. They wore their Ford badge on their shirts in the streetcars on the way to work or on their suits in church on Sundays. It meant something to have a job there. Once through the factory gate, however, the work was intense and often dangerous and unhealthy. Ford himself described repetitive factory work as “a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind,” yet he was firmly convinced strict control and tough discipline over the average worker was necessary to get anything done (Ford, as cited in Martelle, 2012:73). He combined the regimentation of the assembly line with increasingly autocratic management, strictly and often harshly enforced. You couldn’t talk on the line in Ford plants — you were paid to work, not talk — so men developed the “Ford whisper” holding their heads down and barely moving their lips. The Rouge employed 1,500 Ford “Service Men,” many of them ex-convicts and thugs, to enforce discipline and police the plant.

At a time when economic progress seemed as if it would go on forever, the U.S. stock market drove over a cliff in October 1929, and paralysis soon spread throughout the economy. Few places were as shaken as Detroit. In 1929, 5.5 million vehicles were produced, but just 1.4 million rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines three years later in 1932 (Martelle, 2012:114). The Michigan jobless rate hit 40 percent that year, and one out of three Detroit families lacked any financial support (Lichtenstein, 1995). Ford laid off tens of thousands of workers at the Rouge. No one knew how deep the downturn might go or how long it would last. What increasingly desperate people did know is that they had to feed their family that night, but they no longer knew how.

On March 7, 1932 — a bone-chilling day with a lacerating wind — 3,000 desperate, unemployed autoworkers met near the Rouge plant to march peaceably to the Ford Employment Office. Detroit police escorted the marchers to the Dearborn city line, where they were confronted by Dearborn Police and armed Ford Service Men. When the marchers refused to disperse, the Dearborn police fired tear gas, and some demonstrators responded with rocks and frozen mud. The marchers were then soaked with water from fire hoses and shot with bullets. Five workers were killed, 19 wounded by gunfire, and dozens more injured. Communists had organized the march, but a Michigan historical marker makes the following observation: “Newspapers alleged the marchers were communists, but they were in fact people of all political, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.” That marker now hangs outside the United Auto Workers Local 600 union hall, which represents workers today at the Rouge plant.

Five days later, on March 12, thousands of people marched in downtown Detroit to commemorate the demonstrators who had been killed. Although Rivera was still in New York, he was aware of the Ford Hunger March before it took place and told Clifford Wight, his assistant, that he was eager “not [to] miss…[it] on any account” (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Both he and Kahlo had marched with workers in Mexico and embraced their causes. Rivera had captured their lives as well as their protests in his murals in Mexico.

As it turned out, they missed both the march and the commemoration. Instead, the following month Kahlo and Rivera’s train pulled into the Michigan Central Depot, where Wilhelm Valentiner met them. They were taken to the Ford-owned Wardell Hotel next to the Detroit Institute of Arts. The DIA was the anchor of a grass-lined and tree-shaded cultural center several miles north of downtown. The Ford Highland Park Plant, where the automobile age began with the Model T and the moving assembly line, was four miles further north on the same street. Less than a mile northwest was the massive 15-story General Motors Building, the largest office building in the United States when it was completed in 1922, designed by the noted industrial architect Albert Khan, who also created the Rouge. Huge auto production complexes such as Dodge Main or Cadillac Motor — where I would serve my apprenticeship decades later — were not far away.

Valentiner had written Rivera stating, “The Arts Commission would be pleased if you could find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motif suggesting the development of industry in this town. But in the end, they decided to leave it entirely to you” (Beal, 2010:35). Beal points out “that what Valentiner had in mind at the time may have been something like the Helen Moody Wills paintings, something that had an allegorical slant to it. They were to get something completely different” (Beal, 2010:35). Edsel Ford emphasized he wanted Rivera to look at other industries in Detroit, such as pharmaceuticals, and provided a car and driver for Rivera and Kahlo to see the plants and the city.

But when Rivera visited the Rouge plant, he was mesmerized. He saw the future here, despite the fact that the plant had been hard hit by the Depression: the complex had been shuttered for the last six months of 1931, and thousands of workers had been let go before he arrived (Rosenthal, 2015:67). His fascination with machinery, his respect for workers, and his politics fused in an extraordinary artistic vision, which he filled with breathtaking technical detail. He had found his muse.

Rivera took on the seemingly impossible task of capturing the sprawling Rouge plant in frescoes. The initial commission of two large-format frescoes rapidly expanded to 27 frescoes of various sizes filling the entire room from floor to ceiling. Rivera spent the next two months at the manufacturing complex drawing, pacing, photographing, viewing, and translating these images into large drawings — “cartoons” — as the plans for the frescoes. He demonstrated an exceptional ability to retain in his head — and, I suspect, in his dreams — what he would paint.

Rivera’s Vast Masterpieces

Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals are anchored in a specific time and place — a sprawling iconic factory, the Depression decade, and the Motor City — yet they achieve the universal in a way that transcends their origins. Rivera painted workers toiling on assembly lines amid blast furnaces pouring molten iron into cupolas, and through the alchemy of his genius, the art still powerfully — even urgently — speaks to us today. The murals celebrate the contribution of workers, the power of industry, and the promise and peril of science and technology. Rivera weaves together Aztec myths, indigenous world views, Mexican culture, and U.S. industry in a visual tour-de-force that delights, challenges, and provokes. The art is both accessible and profound. You can enjoy it for an afternoon or intensely study it for a lifetime with a sense of constant discovery.

Roberta Smith points out that the murals “form an unusually explicit, site-specific expression of the reciprocal bond between an art museum and its urban setting” (Smith, 2015). Over time, the frescoes have emerged as a visible and vital part of the city, becoming part of Detroit’s DNA. Rivera’s art has been both witness to and, more recently, a participant in history. When he began the project in late spring 1932, Detroit was tottering at the edge of insolvency, and 80 years later, the murals witnessed the city skidding into the largest municipal bankruptcy in history in 2013. A deep appreciation for the murals and their close identification with the spirit and hope of Detroit may have contributed to saving the museum this second time around.

I still vividly remember my own reaction when I first saw the murals. As a young boy, the Rouge, the auto industry, and Detroit seemed to course through our lives. My grandfather Philip Chapman, who was hired at Ford’s Highland Park plant in 1914, wound up spending most of his working life on the line at the Rouge. As a young boy, I watched my grandmother Sophie pack his lunch and fill his thermos with hot coffee before dawn as he hurried to catch the first of three buses that would take him to the plant. When my father, Max, came to Detroit three decades later in the mid-1940s to marry my mother, Rose — they had met on a subway while she was visiting New York City, where he lived — he worked on the line at a Chrysler plant on Jefferson Avenue.

One weekend, when I was 10 or 11 years old, my father took me to see the murals. He drove our 1950 Ford down Woodward Avenue, a broad avenue that bisected the city from the Detroit River to its northern border at Eight Mile Road. Woodward seemed like the main street of the world at the time; large department stores — Hudson’s was second only to Macy’s in size and splendor — restaurants, movie theaters, and office buildings lined both sides of the street north from the river. Detroit had the highest per capita income in the country, a palpable economic power seen in the scale of the factories and the seemingly endless numbers of trucks rumbling across the city to transport parts between factories and finished vehicles to dealers.

We walked up terraced white steps to the main entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts, an imposing Beaux-Arts building constructed with Vermont marble in what had become the city’s cultural center. As we entered the building, the sounds of the city disappeared. We strolled the gleaming marble floors of the Great Hall, a long gallery topped far above by a beautiful curved ceiling with light flowing through large windows. Imposing suits of medieval armor stood guard in glass cases on either side of us as we crossed the Hall, passed under an arch, and entered a majestic courtyard.

We found ourselves in what is now called the Rivera Court, surrounded on all sides by the “Detroit Industry” murals. The impact was startling. We weren’t simply observing the frescoes, we were enveloped by them. It was a moment of wonder as we looked around at what Rivera had created. Linda Downs captured the feeling: “Rivera Court has become the sanctuary of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a ‘sacred’ place dedicated to images of workers and technology” (Downs, 1999:65). I couldn’t have articulated this sentiment then, but I certainly felt it.

The size, scale, form, pulsing activity, and brilliant color of the paintings deeply impressed me. I saw for the first time where my grandfather went every morning before dawn and why he looked so drawn every night when he came home just before dinner. Many years later, I began to appreciate the art in a much deeper way, but the thrill of walking into the Rivera Court on that first visit has never left. I came to realize that an indelible dimension of great art is a sense of constant discovery and rediscovery. The murals captured the spirit of Detroit then and provide relevance and insight for the times we live in today.

Beal points out that Rivera “worked in a heroic, realist style that was easily graspable” (Beal, 2010:35). A casual viewer, whether a schoolboy or an autoworker from Detroit or a tourist from France, can enjoy the art, yet there is no limit to engaging the frescoes on many deeper levels. In contrast, “throughout Western history, visual art has often been the domain of the educated or moneyed elite,” Jillian Steinhauer wrote in the New York Times. “Even when artists like Gustave Courbet broke new ground by depicting working-class people, the art itself still wasn’t meant for them” (Steinhauer, 2019). Rivera upended this paradigm and sought to paint public art for workers as well as elites on the walls of public buildings. By putting these murals at the center of a great museum in the 1930s through the efforts of Wilhelm Valentiner and Edsel Ford — and more recently, under Graham Beal and the current director Salvador Salort-Pons — the Detroit Institute of Arts opened itself and the murals to new Detroit populations. Detroit is now 80-percent African American, the metropolitan area has the highest number of Arab Americans in the United States, and the Latino population is much larger than when Rivera painted, yet the murals retain their allure and meaning for new generations.

Upon entering the Rivera Court, the viewer confronts two monumental murals facing each other on the north and south walls. The murals not only define the courtyard, they draw you into the engine and assembly lines deep inside the Rouge. The factory explodes with cacophonous activity. The production process is a throbbing, interconnected set of industrial activities. Intense heat, giant machines, flaming metal, light, darkness, and constant movement all converge. Undulating steel rail conveyors carry parts overhead. There were 120 miles of conveyors in the Rouge at the time; they linked all aspects of production and provide a thematic unity to the mural. And even though he’s portraying a production process in Detroit, Rivera’s deep appreciation of Mexican culture and heritage infuses the frescoes. An Aztec cosmology of the underworld and the heavens runs in long panels spanning the top of the main murals and similar imagery appears throughout the frescoes.

On the north wall, a tightly packed engine assembly line, with workers laboring on both sides, is flanked by two huge machine tools — 20 feet or so high — machining the famed Ford V8 engine blocks. Workers in the foreground strain to move heavy cast-iron engine blocks; muscles bulge, bodies tilt, shoulders pull in disciplined movement. These workers are not anonymous. At the center foreground of the north wall, with his head almost touching a giant spindle machine, is Paul Boatin, an assistant to Rivera who spent his working life at the Rouge. He would go on to become a United Auto Workers (UAW) organizer and union leader. Boatin had been present at the Ford Hunger March on that disastrous day in March 1932 and still choked up talking about it many decades later in an interview in the film The Great Depression (1990).

In the foreground, leaning back and pulling an engine block with a white fedora on his head may have been Antonio Martínez, an immigrant from Mexico and the grandfather of Louis Aguilar. A reporter for the Detroit News, Aguilar describes how fierce, at times ugly, pressures during the Great Depression forced many Mexicans to leave Detroit and return to their homeland. The city’s Mexican population plummeted from 15,000 at the beginning of the 1930s to 2,000 at the end of the decade. If the figure in the mural is not his grandfather, Aguilar writes “let every Latino who had family in Detroit around 1932 and 1933 declare him as their own” (Aguilar, 2018).

A giant blast furnace spewing molten metal reigns above the engine production, which bears a striking resemblance to a Charles Sheeler photo of one of the five Rouge blast furnaces. The flames are so intense, and the men so red, you can almost feel the heat. In fact, the process is truly volcanic and symbolic of the turbulent terrain of Mexico itself. It brings to mind Popocatépetl, the still-active 18,000-foot volcano rising to the skies near Mexico City. To the left, above the engine block line, green-tinted workers labor in a foundry, one of the dirtiest, most unhealthy, most dangerous jobs. Meanwhile, a tour group observes the process. Among them in a black bowler hat is Diego Rivera himself.

On the south wall, workers toil on the final assembly line just before the critical “body drop,” where the body of a Model B Ford is lowered to be bolted quickly to the car frame on a moving assembly line below. Once again, through his perspective Rivera draws you into the line. A huge stamping press to the right forms fenders from sheets of steel like those produced in the Rouge facilities. Unlike most of the other machines Rivera portrays, which are state of the art, this press is an older model, selected because of its stylized resemblance to an ancient sculpture of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess of life and death (Beale, 2010:41; Downs, 1999:140, 144).

On the left is another larger tour group, which includes a priest and Dick Tracy, a classic cartoon character of the era. The Katzenjammer Kids — more comic icons of the time — are leaning on the wall watching the assembly line move. The eyes of most of the visitors seem closed, as if they were physically present, but not seeing the intense, occasionally brutal, activity before them. Rivera, in effect, is giving us a few winks and a nod with cartoon characters and unobservant tourists.

Underneath the large murals on both walls are six gray panels depicting the daily life of workers. These panels “are reminiscent of the predella panels of Italian Renaissance altarpieces which contained a border under the main images and depicted scenes in the life of the religious figures represented above” (Downs, 1999:92). Two of the panels stand out in particular. On the north wall, the third panel from the left shows Henry Ford lecturing apprentices. The V-8 engine in front of him looks like a hairless dog with the gearshift as its tail. With a forefinger raised, “Ford is making a gesture commonly used in Renaissance portraits of John the Baptist, which conveys the sense that a greater one is yet to come” (Beal, 2010). On the south wall, the last predella panel shows workers cashing their paychecks at an armored car at the end of a shift and walking slightly bent in overcoats on the overpass spanning Miller Road to buses, trolleys, and parked cars on their way home.

A photo of this overpass would be seen around the world four years later in May 1937, when three organizers from the fledgling UAW union sought to hand out leaflets to Ford workers. The organizers were beaten badly by thugs from the Ford Service Department. A Detroit News photographer captured both the beating and the bloody aftermath in now iconic photos. One of the three was Walter Reuther, who had been a young toolmaker at the Rouge when Rivera came to Detroit and was fired that year, likely for organizing. He would go on to lead the UAW for two decades and become one of the most influential, innovative, and effective labor leaders in the 20th century.

The assembly lines are cramped in the monumental murals: workers stretch and struggle in tandem, no smiling and no talking. Many critics have written that Rivera idealizes or romanticizes work and workers. I would disagree. The art allows very different interpretations. One can view workers on the line in tight, pressured spaces as doing hard, alienating, soul-destroying work — often unhealthy and dangerous — or one can view the same scene as a highly efficient combination of people and machines laying the basis for a world of material abundance. In fact, one can share both perspectives. For Rivera, who still viewed himself as a communist, despite having been expelled from the Mexican Communist Party, this complex industrial process laid the material basis for a socialist society. The frescoes could just as easily be praised — and were — by industrialists for showing the miraculous nature of mass production and capitalism. What is clear is that Rivera pays homage to what workers do and to the dignity of work while simultaneously offering a tribute to advanced mass production.

“And, if you turn around to face the west wall, that panel is all about man and the machine,” Graham Beal observes. “This sets up the series of extraordinary dualities which are the essence of the Rivera mural as a whole. On one side, there is agriculture and nature; on the other, there is man and the machine” (Beal, 2010:37). These dualities add excitement and intellectual tension to the murals: are we looking at satanic mills or industrial miracles? And the frescoes pose stark, urgent choices for viewers: technology for passenger flight or warplanes; the brilliance of science for vaccines or to build chemical bombs?

Jackboots were marching through Europe as Rivera painted: Mussolini was in power in Italy, and Hitler was about to seize power in Germany. “Rivera also brings together the two hemispheres: North and South,” Beal writes about the west wall. “On one side, rubber is being taken from tropical trees in Brazil, on the other is the Detroit skyline” (Beal, 2010:37). Those trees could have been the sprawling rubber plantation Ford had built in Brazil referred to as “Fordlândia.”

Mexican curator (and Rivera’s grandson) Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera comments that a “more obscure dimension [to the murals] is a mythological narrative aimed at exploring the philosophical concept of existence from the perspective of Nahua philosophy (the Nahuatl being the indigenous people of central Mexico, often referred to as the Aztecs), and a third dimension shows the development of the human being from the Rosicrucian (Masonic) viewpoint. These later two interpretations are interlinked” (Coronel, 2015:128). Coronel also points out that “the fresco on each wall of the DIA murals is divided into three sections, which, though the result of the structural divisions of the building, ideally fulfill Rivera’s conception of representing the three realms of the pre-Hispanic worldview: sky, earth, and underworld” (Coronel, 2015).

However, Rivera shifts this order, beginning with the making of cars on Earth, he then proceeds to the underworld and finally presents the sky. Above the north and south frescoes illustrating automobile production are long rectangular panels that portray the minerals of the earth. A third layer above this one on each wall features two female nudes lying on the ground digging minerals from the earth with a volcano between them. From the volcano, huge hands reach toward the sky grasping more minerals. A total of four female nudes in the top panels represent Rivera’s vision of four races — red and black on the north wall and white and yellow on the south wall.

To the right and left of the top panel on the north wall are two smaller frescoes. To the left is “Manufacture of Poisonous Gas Bombs,” with figures wearing gas masks; below is a small panel in which cells are suffocated by poison gas, recalling the horrors of World War I. To the right is “Vaccination and Healthy Human Embryo,” portraying a doctor vaccinating a child attended by a nurse. The two frescoes present a choice in the use of science: for life or death; for peace or war.

|

|

The vaccination panel, however, is arguably the most controversial part of the murals. Downs writes that “the composition of this panel is directly taken from the Italian Renaissance form of the nativity, where the biblical figures of Mary and Joseph and Jesus are depicted in the foreground and the three wise men in the background” (Downs, 1999:111). This panel was so problematic that Catholic groups demanded the murals be destroyed even prior to the opening in March 1933, and these protests against Rivera’s art continued for more than two decades into the late 1950s.

Many critics have viewed the frescoes as presenting a mythical vision of the Rouge in 1932. Roberta Smith calls them “an idealized ode to the city in 27 frescoes” (Smith, 2015). While there is certainly truth in the observation, it distorts as well as reveals. In my view, a more accurate way to describe Rivera’s approach might be “magical realism” (with all due respect to Latin American literature). Rivera clearly starts with the hard truth of the factory floor of the Rouge. After visiting the frescoes, the Chrysler Motor Company chief engineer reported that “[Rivera] has fused together, in a few feet, sequences of operations which are actually performed in a distance of at least two miles, and every inch of [the] work is technically correct” (Rosenthal, 2015:66). That achievement contributes to the “realism” of the mural.

The “magical” part comes from the fact that Rivera portrayed the Rouge as it had been before the crash in 1929 and, more importantly, what it could be in the future, not what it was in the midst of devastating economic collapse. At the time Rivera painted, Ford had furloughed tens of thousands of workers, slashed wages, and sped up the work of those who remained. The economic energy Rivera paints is a vision of what could be, not the reality of what was. He didn’t seek to capture the reality of the moment, but rather what the future might hold. He channeled the spirit of the Rouge to capture the spirit of Detroit.

In addition, Rivera included a multicultural group of workers on the line. This mix of workers also didn’t occur during this period. Ford employed many more African Americans than other automakers — about 10 percent of his workforce — but they were almost entirely confined to the most dangerous and unhealthy work on the coke ovens, blast furnaces, and foundries.

Rivera embraced four broad perspectives that shaped the “Detroit Industry” murals. First, his passion for machinery and advanced technology; second, his respect and admiration for workers; third, his surprising personal connection with Henry Ford; and, finally, his belief that advanced capitalism could lay the basis for a socialist society. Coronel has pointed out that “Rivera was fascinated by modernity — furnaces and smokestacks, laborers hard at work, incessant mass production lines that flowed like rivers of fire” (Coronel, 2015:126).

When he encountered the scale and reach of the Rouge, Rivera moved beyond fascination and became absolutely enchanted by the complex and then immersed within it. He wanted to artistically convey his overwhelming passion and, at the same time, capture the technical achievements with great rigor. For Rivera, unlike the artist and photographer Charles Sheeler, workers were at the heart of the production process. He was determined to capture the dignity of the worker and his admiration for the value of what the worker did. At the same time, he unflinchingly portrayed the pain and sacrifice of factory work. While his figures are stylized and figurative, they are not “socialist realism.” The viewer doesn’t exactly want to burst into song, grab a wrench, and march off to the factory.

Looking back at the murals, I would have liked to ask my grandfather Phillip what he thought of the art. It never occurred to me at the time, and in retrospect, I don’t think my grandfather ever entered the museum. He worked hard at the plant, and when there was a day off, we would go to Belle Isle, an island park in the middle of the Detroit River where you saw (and smelled) the U.S. Rubber Company plant on the Detroit side and a large Ford plant in Windsor, Ontario, on the other side.

Rivera’s personal connection with Henry Ford was a surprise to many, if not a total mystery. Ford, of course, was a global folk hero. In a 1927 poll, he was ranked among the three most important people who have ever lived, trailing only Jesus and Napoléon. He was also held in high esteem in the Soviet Union, which impressed Rivera during his 1927 visit to Moscow, where he saw photos of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Ford in workers’ homes. Ford had built two sprawling auto assembly plants in Russia, where he was well known. Ford and Rivera shared a deep interest in technology and a consuming interest in mechanics, and Ford could be folksy and charming. In his autobiography, My Art, My Life, Rivera recalls Ford saying, after the two had shared a conversation, “I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed our meeting,” and then himself replying that he “felt equal warmth.” He then went on to write, “I regretted that Henry Ford was a capitalist and one of the richest men on earth.” This fact, he felt, limited his ability to praise Ford. “Otherwise, I should have attempted to write a book presenting Ford as I saw him, a true poet and artist, one of the greatest in the world” (Rivera, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:56).

This vision of Ford neglected a number of issues with which Rivera must have been familiar. Ford, for example, was a virulent and public anti-Semite. He was strongly opposed to unions and had responded in a murderous way to the Hunger March at the Rouge the month before Rivera and Kahlo arrived in Detroit. And Ford had made public statements that the Depression was compounded by workers’ lack of initiative to just go out and get a job. Nonetheless, Rivera felt “Marx made theory … Lenin applied it with his sense of large-scale social organization … and Henry Ford made the work of the socialist state possible,” while his own role was to “paint the story of the new race of the age of steel” (Rivera, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:62). He clearly felt that by concentrating on the extraordinary technical achievement of the Rouge, he was paying homage to the material basis for a new society.

Rivera had painted strikes, revolutionary struggles, worker and peasant movements, and Marx in earlier murals in Mexico and would paint them again in the United States. I suspect he felt that including the Hunger March in this mural would detract from his core vision and the lasting meaning he wanted it to have. Did he fear that it might jeopardize the project itself? Probably. He fully understood upending the apple cart was a real possibility and was not about to risk it.

Rivera did receive sharp criticism at the time from some for what he didn’t portray, such as the anti-union violence. This criticism may have propelled him to include these themes in his Rockefeller Center mural the next year in New York, which wound up being destroyed. In Detroit, however, it was not a historical rendering of the present Rivera was after, but a vision of what the future could hold.

Moments of criticism remain today. At the legendary UAW Local 600, which represents workers at the Rouge plant, many workers and union leaders are proud of the murals. The local president, Bernie Ricke, proudly displays reproductions in his office. He has also shown huge reproductions in the large main hall of the local and points out that a nearby public library also exhibits an image of the murals. Nonetheless, on the local’s Web site a brief comment both extolls the art and reflects on what’s not there: “On March 21, 1933, Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry opened at the Detroit Institute of the Arts. It’s a stunning work of art, showing the workers at the Ford Rouge Plant, but it is just as remarkable for what it doesn’t show” (UAW, n.d.).

As the opening date of the frescoes approached back in March 1933, the controversy over Rivera’s art seemed to escalate. At a time of social tension and conflict during the Great Depression and only a year after the shootings at the Hunger March, some Detroiters were outraged that a communist and a Mexican had been chosen to paint these murals in the DIA. They saw communist themes running through the murals, even if they weren’t quite sure where or how. Beyond these themes, there were no shortages of other criticisms.

Linda Downs indicates other flashpoints: “[T]here were nudes in it — and a laboratory with a child being vaccinated, painted in the style of a nativity scene. As for the upper classes, they didn’t like the working classes invading their museum. They were offended by that” (Downs, as cited in The Detroit News, 2015). The Detroit News called the frescoes “foolishly vulgar” and miraculously concluded that they were “a slander to Detroit workingmen” (The Detroit News, 2015). Taking the side of these workers, a rare stance of the paper in these years, the newspaper called for the frescoes to be removed.

More recent information seems to indicate the museum itself may have contributed to the controversy to boost attendance. If true, this approach was a risky strategy. Nonetheless, the attendance reflected great excitement, whether because of the controversy or despite it: on the Sunday after the opening, 10,000 people crammed into the museum to view the art.

The critics have faded into history, but the murals remain more vital and important than ever.

Kahlo’s Tiny Masterpieces

While in Detroit, Frida Kahlo completed eleven works, including five paintings. Along the way, she developed a stunning style, looking deep into her soul and portraying the pain and trauma she felt. As The New Yorker pointed out, for Kahlo “painting remained first and foremost a vehicle of personal expression” (Hellman & Ross, 1938).

Kahlo had a physically painful life from a very young age. She was diagnosed with polio when she was six years old, and in 1925, she was in a horrific bus accident that nearly killed her. She was unable to walk for three months and then had multiple operations, prosthetics, and grueling complications for the rest of her life.

Kahlo’s art drew on many diverse sources but particularly pre-Columbian and folk art rooted in Mexico. Tere Arcq, former Chief Curator at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, explains that these influences can be seen in the ways in which Kahlo portrayed traditional objects, “in the colors of her palette, and in the appropriation of certain compositional schemes and themes” (Arcq, 2019:42). Her work visibly reflected Surrealist approaches and imagery in 1932 when, Arcq tells us, “she was in Detroit and had gone through a harrowing abortion” (Arcq, 2019:39). Nonetheless, in the 1938 press release for her exhibition, Kahlo herself claimed, “I never knew I was a Surrealist until André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was one. I myself still do not know what I am” (Grimberg, 2019:30).

Both her feminism and nationalism shone in the way she dressed. Arcq argues that Kahlo’s “portraying herself as a Tehuana woman is a clear discourse around her stance on gender politics, given that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec was the only place in Mexico that still had a matriarchal culture” (Arcq, 2019:42). Early in her time in Detroit, Kahlo painted “Self Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States.” In the small oil on metal painting, she portrays herself standing in the foreground on a stone block, wearing a bright pink dress. The painting is defined by the duality of Mexico on the left and the United States on the right.

The Mexican side likewise portrays a second duality of a fierce sun and a pensive quarter moon both shrouded in clouds. A finger from each cloud touches, sending forth a lightning bolt to the ruin of a massive Mexican pyramid below. Three small sculptures sit on the ground before it. The fertile earth is filled with flowers and plants blooming and extending roots. This final duality points out that the culture is ancient and Mexico still lives.

The United States is on the right. Skyscrapers, industrial air ducts, and the towering stacks of a Ford factory — likely the Rouge — define the scene. Smoke pours out of the stacks into the sky covering a U.S. flag in haze. Technology dominates everything, including electrical cords that extend into the ground with one plugged into the stone on which she is standing.

One of Kahlo’s hands holds a Mexican flag towards Mexico and the other, a cigarette pointing towards the United States. She is gazing in the direction of Mexico. “Kahlo clearly wanted to challenge Rivera’s worldview of a united Americas,” Rosenthal writes. “Her own position was that Mexico and the United States were too spiritually distinct to ever find common ground” (Rosenthal, 2015:101). Nonetheless, the wires of a U.S. fan snake underground to touch the roots of a Mexican plant.

I was taken with “Self Portrait on the Borderline” for many years before I actually encountered the painting in person. I first saw it at the Detroit Institute of Arts in the 2015 exhibit “Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo: The Detroit Experience.” When I glimpsed it across the gallery, I was startled by its small size, about 12x14 inches. When you approach a Kahlo painting, the intensity of her art pulls you into the work and fully engages you with color, texture, and artistic vision. Roberta Smith captures the power of Kahlo’s art when she writes “[her] small paintings are portable altarpieces for private devotion and a high point of Surrealism that speaks to us still” (Smith, 2015).

A second small oil on metal painting she did in Detroit after her miscarriage — what likely was a self-induced abortion that went awry — is harrowing. She was admitted to the hospital and painted “Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit” shortly afterward, and the painting carries the immediacy and horror of her experience. The work shows her lying naked on a hospital bed in a pool of blood. Six surreal objects are attached to her by umbilical cords, three flying above — including a male fetus — and three objects lying on the ground. The experience is anchored in Detroit. The Rouge plant is portrayed at the horizon in the distance, and lest we forget, “Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit” is written on the side of the bed.

In his autobiography, Rivera discusses the impact of this tragic event on her art: “Immediately thereafter, she began work on a series of masterpieces which had no precedent in the history of art — paintings which exalted the feminine qualities of endurance to truth, reality, cruelty, and suffering.” And he proclaims, “Never before had a woman put such agonized poetry on canvas as Frida did at this time in Detroit” (Rivera, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:97). In a very real way, Kahlo’s artistic sensibility and Rivera’s artistic vision likely was at least a point of reference, if not an influence on the other, given the intensity and turbulence of their relationship.

“When she arrived [in Detroit], she was well along in synthesizing the influences of Mexican folk art and Surrealism into a mature vision,” Roberta Smith writes. “But in many ways, the miscarriage she suffered while in Detroit spurred the searing form of self-representation that is her contribution to art history” (Smith, 2015).

A Few Concluding Remarks

Almost nine decades have gone by since Rivera and Kahlo painted in Detroit. Yet, Rivera’s dream of a popular international art has found an enthusiastic new audience, and Kahlo’s art is not only highly regarded by critics, but her style has seeped into popular culture in a major way.

At the time when there was a move to destroy the murals shortly after they opened, noted lyric soprano Dora Lappin told the Washington Post, “To me there is something majestic and inspiring about those powerful hands of labor and industry Rivera has painted on the wall of the courtyard. They are reaching upward toward … a day when the cultural life will be available to every person in the city” (Lappin, as cited in The Washington Post, 1934:13). That day Lappin was hoping for has not arrived, but at least we are looking in that direction.

For me, the murals have been a lifetime companion. I remember visiting them occasionally while in high school, seeking to impress friends by saying I had seen them before (but neglecting to point out that visit had been when I was eleven and with my father). I also sought them out at times of great trauma, such as the 1967 Rebellion in Detroit, when the city was in flames for a week and 44 people died. I remember going to see the murals several weeks later. I was an apprentice then, working at a Cadillac stamping plant on Detroit’s east side and living in Highland Park, a little more than a mile from where the upheaval had started early one Sunday morning. You could see the flames of the city from the roof of the plant the Monday morning after, and National Guard troops were lining Woodward less than a half block from where I lived. The technical virtuosity of the frescoes fascinated me then, as I was working on similar stamping presses and engine lines, and the brilliance of the art moved me. The murals anchored the troubled present with an optimistic vision of the future painted during tough, uncertain times.

After visits too numerous to count over the years, a relatively more recent occasion stands out. The Center for Latin American Studies convened a session of the U.S.–Mexico Futures Forum in Detroit, bringing about a dozen people from the United States and Mexico to discuss renewable energy in the industrial heartland. We had a small dinner in the Rivera Courtyard enveloped by the frescoes. There was something inspiring about seeing this art during hard economic times for the city and imagining an industrial transformation and a sustainable future with new solar and hydrogen technologies utilizing the skills, innovation, talent, and industrial infrastructure that Rivera had portrayed so long ago. And there was something particularly moving about having Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas as a participant. Cárdenas had grown up with Rivera in Mexico and may have been seeing these murals for the first time.

Detroit is in the midst of an important cultural and economic revival, but decades of neglect and powerful economic and social forces beyond the city and the region continue to throttle opportunity and make life tough for many, if not most, Detroiters. Yet new genera-tions continue to visit the Garden Court to see Rivera’s remarkable “Detroit Industry” murals and rediscover an important dimension of their city’s roots.

The murals have moved from a point of sharp controversy through a period when they were tolerated but ignored to a point of new appreciation and great civic pride. This stature was unexpectedly confirmed in an unusual format after the city suffered through the 2008-2009 economic collapse. After General Motors and Chrysler had skidded into bankruptcy, both companies emerged from the abyss, restructured, and are now successful. The newly renamed Fiat Chrysler ran a Super Bowl commercial at halftime in 2011 in the early days of recovery. The “Imported from Detroit” ad featured Detroit-born rapper Eminem. The commercial begins with Eminem driving through an industrial area of Detroit, past oil refineries spewing smoke and abandoned buildings, towards downtown Detroit. As he passes a giant sculpture of the forearm and fist of Joe Lewis — the 1930s world champion African American boxer from Detroit — Eminem points out, “it’s the hottest fires that make the hardest steel.” Then we are looking at workers building engines on the north panel of the “Detroit Industry” murals in three stunning shots, as Eminem continues: “Add hard work and conviction and the know-how that runs generations deep in every last one of us — that’s who we are. That’s our story.”

Diego Rivera captured what Detroit workers did in 1932, and his art has continued to inspire through trauma and recovery, as has the art of Frida Kahlo in a much different, though equally profound, way. The lives and art of both Kahlo and Rivera were firmly rooted and nurtured in Mexico. When they died — she in 1954 and he in 1957 — their bodies lay in state in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, which has emerged as a cathedral for a culture and a country in the historical heart of Mexico City. Shortly before her death, Kahlo participated from a wheelchair in a demonstration against a U.S.-sponsored coup in Guatemala, and her casket was covered with a large flag bearing a hammer and sickle while she lay in state. In her funeral cortege, Rivera walked side-by-side with Lázaro Cárdenas, the beloved and transforming president of Mexico (1934-1940).

The lasting power and meaning of their art has found new audiences far beyond Mexico. At a time when incendiary rhetoric and talk of walls has been so prominent, their artistic vision has moved beyond borders and been deeply appreciated in Mexico, the United States, and throughout the world.

Harley Shaiken is the Class of 1930 Professor of Letters and Science and Chair of the Center for Latin American Studies at UC Berkeley. This article is based on a talk presented in Mexico City in May 2019 organized by a new collaboration between the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the Jenkins Graduate School of the Universidad de las Américas, the Mexican Museum in San Francisco, and CLAS.

References

Aguilar, L. (2018, March 21). Opinion: Rivera’s DIA mural comes alive with family lore. The Detroit News. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.detroitnews.com/story/opinion/2018/03/21/rivera-mural-latinos/33162181/.

Arcq, T. (2019). Mexico and Surrealism: “Communicating Vessels.” In Arcq, T., Field, J., Grimberg, S., O’Neill, E. (2019). Surrealism in Mexico. New York, NY: Di Donna Galleries, LLC.

Beal, G.W.J. (2010, Spring-Summer). Mutual Admiration, Mutual Exploitation: Rivera, Ford and the Detroit Industry Murals. Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, 34-43.

Controversy raged around debut of Rivera's murals (2015, March 13). The Detroit News. (Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/wayne-county/2015/03/12/controversy-raged-around-debut-riveras-murals/70253934/.)

Coronel Rivera, J.R. (2015). “April 21, 1932.” In Rosenthal, M. Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo in Detroit. Detroit, MI and New Haven, CT: Detroit Institute of Arts and Yale University Press.

Dickerman, L, Indych-López, A., Aviram, A., Albertson, C., & Roberts, J. (2011). Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art. New York, NY: The Museum of Modern Art.

Downs, L. Bank. (1999). Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals. Detroit, MI and New York, NY: Detroit Institute of Arts and W. W. Norton and Company.

Downs, L. (2015). “The Director and the Artist: Two Revolutionaries.” In Rosenthal, M. Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo in Detroit. Detroit, MI and New Haven, CT: Detroit Institute of Arts and Yale University Press.

Farago, J. (2019, February 7). Frida Kahlo’s Home Is Still Unlocking Secrets, 50 Years Later. The New York Times. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/arts/design/frida-kahlo-review-brooklyn-museum.html.

Fitzgerald, F.S. (2017, March 7). The Crack-Up, Part I. Esquire. (Original work published February, 1936). Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/a4310/the-crack-up/#ixzz1Fvs5lu8w.

Freeman, Joshua B. (2018) Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W.H. Norton and Company.

Grimberg, S. (2019). Mexico Reflected on Andre Breton’s Mirror. In Arcq, T., Field, J., Grimberg, S., O’Neill, E. (2019). Surrealism in Mexico. New York, NY: Di Donna Galleries, LLC.

Hellman, G.T., & Ross, H. (1938, November 12). “Ribbon Around Bomb.” The New Yorker. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1938/11/12/ribbon-around-bomb.

Interview with Paul Boatin, conducted by Blackside, Inc. (1990, June 28). The Great Depression [Video file]. Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from http://digital.wustl.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=gds;cc=gds;rgn=main;view=text;idno=boa13968.13933.024.

Lichtenstein, N. (1995). The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor. New York, NY: Harper Collins, Basic Books.

Martelle, S. (2012). Detroit: A Biography. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press, Inc.

Rivera's Art Conception of Industry as Soul of Detroit Defended by Visitor from Auto City: Dora Lappin, Noted Singer, Says It Brought About Cultural Increase. (1934, Feb 15). The Washington Post (1923-1954). Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://search.proquest.com/docview/150454149?accountid=14496.

Rosenthal, M. (2015). Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo in Detroit. Detroit, MI and New Haven, CT: Detroit Institute of Arts and Yale University Press.

Shaiken, H., & Beal, G. (2015, Spring). Diego and Friday in Detroit: An Interview with Graham Beal. Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, 37-45.

Smith, R. (2015, April 3). Review: “Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit.” The New York Times. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/arts/design/review-diego-rivera-and-frida-kahlo-in-detroit.html.

Steinhauer, J. (2019, June 6). In Praise of the Great Majority. The New York Times. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/06/arts/design/moma-workers-and-paintings.html.

Trotter, J. (2019). Workers on Arrival: Black Labor in the Making of America. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

United Automobile Workers (n/d). UAW through the Decades: The 1930s and Before. Retrieved 01/02/2020 from https://uaw.org/members/uaw-through-the-decades/.

Work Projects Administration (WPA) in the State of Michigan & Michigan State Administrative Board. (1941). Michigan: A guide to the wolverine state (American guide series). New York: Oxford University Press.