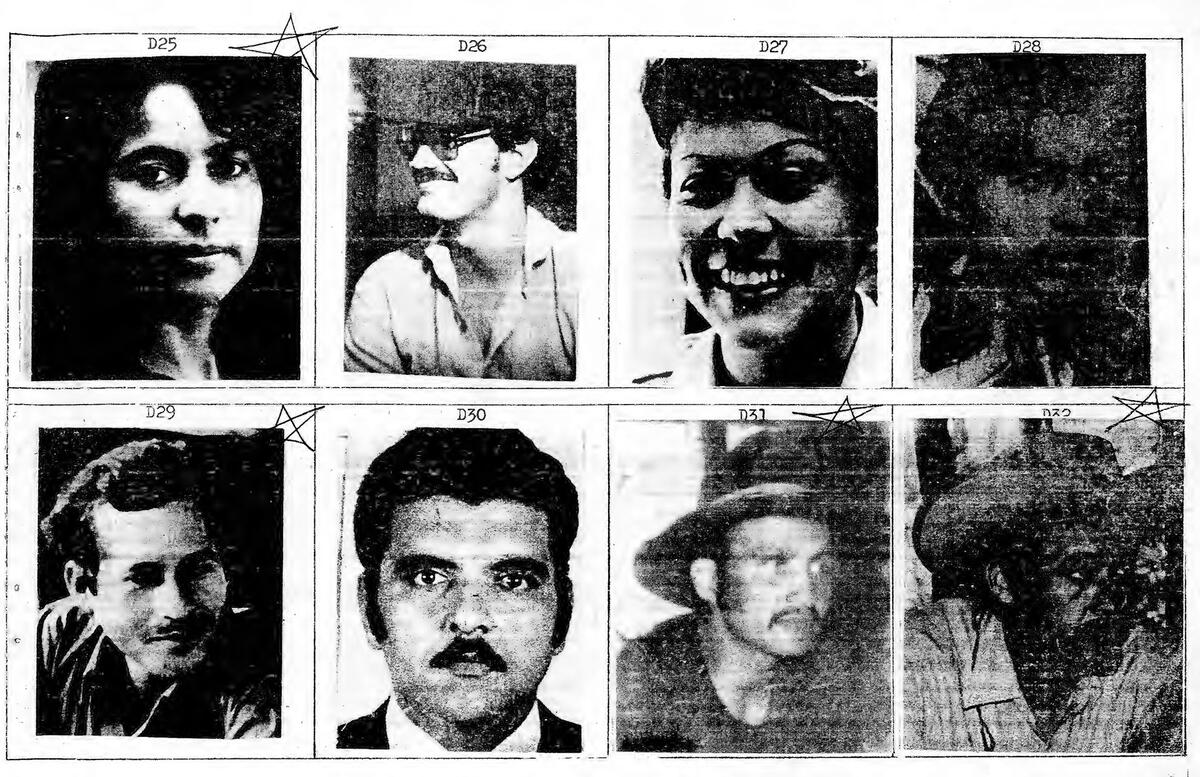

The images have a haunting quality. Some look like studio portraits: fresh-faced young people, shoulders angled artfully toward the photographer, smiles fixed across their lips. Despite the low resolution, one can almost make out the shine on their curls. Others are photos clearly lifted from an ID document — expressions serious, the partial arc of an official stamp sometimes visible in a corner. And mixed among these frozen snapshots of a better time, there are others: mug shots of people backed against a wall or photographed from the side, some with dark circles under their eyes and unkempt hair; others appear bruised. These may have been the last photographs taken of them alive.

At the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights, we have been conducting research on crimes against humanity committed during the Salvadoran armed conflict, working in collaboration with Salvadoran survivors and advocates since 2011. It was early in this initiative that partners first shared with us a digital copy of the “Yellow Book,” a Salvadoran military intelligence document from 1987 that includes the names and photographs of almost 2,000 people identified as “delinquent terrorists.” In some ways, the document looked familiar — as a photographic logbook of state repression, it evokes the infamous “Diario Militar” of Guatemala or the grim pictures from Pol Pot’s S-21 prison — but in other ways, it was entirely new. This document was the first of its kind to come out of El Salvador, providing a never-before-seen window into that country’s bureaucratization of terror.

There was a time, of course, when El Salvador’s human rights record was the subject of worldwide attention. The small country was ground zero for a high-stakes Cold War confrontation between the U.S.-backed government and the Marxist rebels of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Likewise, the modern human rights movement developed its now-familiar approach to data-driven advocacy there, seeking to counter the propaganda that U.S. and Salvadoran authorities produced to explain away mass graves. At war’s end, the UN Truth Commission concluded that more than 75,000 people had been killed between 1980 and 1992, more than 85 percent at the hands of state forces and death squads. Yet, thanks to an amnesty law signed just days after the truth report’s release, to this day no one has been held accountable for these crimes. While Latin American countries from Chile to Guatemala have captured headlines for recent efforts to reckon with legacies of authoritarianism, the human rights effort in and for El Salvador has slipped from leader to laggard.

But this situation may soon change. In the summer of 2016, in a bold and long-awaited ruling, the Constitutional chamber of the Salvadoran Supreme Court struck down the Amnesty Law, ordering the investigation of grave crimes committed by both sides during the war. The decision jump-starts El Salvador’s long-stalled transitional justice process, vindicating victims and their families who have waged decades-long campaigns for justice.

It also poses challenges to a justice system already straining under the burden of addressing contemporary crime in one of the world’s most violent countries. To be sure, the road ahead will not be easy. The country lacks forensic expertise, the victims’ organizations require funding and international support, and the same judiciary we now expect to hear these cases has spent years twiddling its thumbs, despite abundant evidence of widespread war crimes. The military, for its part, remains intransigent in its refusal to open its files, flouting the requirements of El Salvador’s 2013 Public Information Law with apparently little consequence. For all of these reasons, thousands of families still lack access to the most basic information about lost loved ones.

So when I first began to examine the Yellow Book years ago, unlocking its secrets took on an immediate urgency. What fate ultimately befell the people profiled in its pages? And what new knowledge might the book reveal about the workings of state terror? In collaboration with Kate Doyle from the National Security Archive, we authenticated the document, while Salvadoran researchers began to contact survivors and family members of those it named. In partnership with the Human Rights Data Analysis Group, we compared the names in the book to known lists of victims, finding that 43 percent of the names corresponded to reported violations logged in human rights databases.

And slowly, stories began to emerge from the book’s grainy pages: students snatched from street corners by groups of heavily armed men, never to be seen again; labor leaders held for years as political prisoners; professors and church workers, daughters and cousins, rebels and dreamers. Some of the faces started to feel familiar. Haunted by the hope that I could help families find them, I began to comb the archives of declassified U.S. government documents for information about their cases. The search had a needle-in-a-haystack quality: at war’s end, the Clinton administration had ordered the release of more than 10,000 pages of documents containing information, but very few included the kind of details that might help establish the fate of the missing.

When we finally published the Yellow Book on our website in September 2014, the response was powerful. Within three days, our still-sleepy website had attracted more than 80,000 unique views, and we began to receive messages from Salvadorans around the world. Some thanked us for our work, and some offered up stories we hadn’t yet heard about people in the book. Others asked us if we could help find a long-lost son, a sister, a disappeared classmate. “It’s not until now that I see his picture in the book, visibly tired, with signs of having been tortured,” one person wrote about an uncle. “Was his body dumped on the beach in El Playón? Could it be in one of the mass graves at a military barracks? Was he killed in combat, was his body left in the weeds? Could his own companions have killed him in one of their internal purges? These are questions we are left asking ourselves. My grandmother cried for her son until the last day of her life. Please help us find out what happened to him.”

Although estimates place the number of the disappeared in El Salvador in the range of 5,000 to 10,000, the truth is that no one really knows. There has never been a systematic inquiry into the practice of forced disappearance during the conflict, much less a rigorous attempt to locate the remains of the disappeared. In recent months, a new group of young Salvadoran-Americans whose parents were forcibly disappeared during the war have launched a campaign, taking for its poignant title their singular demand: “Our Parents’ Bones.” In conjunction with the Washington Office on Latin America, the Due Process of Law Foundation, and these brave new leaders, our Center for Human Rights helped sponsor a U.S. Congressional briefing on these issues in April 2016, and several of children of the disappeared testified. They shared stories of growth, courage, and resilience, but they also told of lives built on perilously slender filaments of memory stretched across a terrible gaping hole. Psychologists call the trauma faced by families of the disappeared “ambiguous loss.” Without knowing a loved one’s ultimate fate or having the chance to lay their remains to rest, the ability to grieve is forever suspended.

In response to inquiries from Salvadoran survivors, their families, and justice advocates, our research team has filed nearly 300 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with six different U.S. agencies. Over the past three years, we have successfully obtained the release of 181 newly declassified documents, all of which we have shared with survivors and advocates. Sadly, our requests have also resulted in a raft of refusals to respond by government agencies citing national security concerns. Three decades after the incidents in question — and even granted the ability to redact sensitive information from documents prior to their release — federal agencies are still arguing that revealing the truth could endanger the United States.

In one such case, the University of Washington filed suit against the Central Intelligence Agency last fall, becoming the first university in the country to do so. While litigation is still pending, the CIA released more than 400 pages of documents to us in March 2016, offering an unprecedented window into the depth of detail available in the U.S. intelligence archives. One document, for example, describes an upcoming military operation, listing the names of participating units and such details as key latitude and longitude points along their approach to the intended target. This kind of information could be extraordinarily useful for those seeking to find the disappeared.

In recent years, the Obama administration has made use of what Peter Kornbluh terms “declassified diplomacy,” offering to release records relating to South American dirty wars. This transparency is not the result of FOIA requests, but rather of decisions made at the highest levels of the White House and State Department to hand-select documents and deliver them to foreign leaders in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. These documents have helped human rights groups seeking to clarify past crimes, offering new confirmation, for example, that the CIA believed General Pinochet was personally involved in the murders of Chilean leftist Orlando Letelier and his associate Ronni Moffitt on U.S. soil in 1976. However, most of the records declassified in the 1990s were State Department records, and even today, the State Department is the most responsive of the federal agencies that we have approached for information. This response is a good start, but El Salvador’s army effectively governed the country for much of the 1980s. Unsurprisingly, the Salvadoran military shared details of daily operations with its trainers and collaborators in the U.S. military and intelligence community far more frequently than with diplomats at the U.S. Embassy. While the lawsuit has not yet provided us access to all the documents we seek, its initial dividends have confirmed our long-held suspicion that the most valuable information for clarifying past crimes lies in the hands of the agencies least likely to respond to FOIA requests.

Yet the United States was even more heavily involved in El Salvador than in South America. In addition to providing training, equipment, and financial assistance for the Salvadoran forces, the U.S. embedded its own troops within Salvadoran military units, piloted aircraft overland on a daily basis to gather intelligence, and mounted its own propaganda effort to launder the image of the Salvadoran regime in the face of human rights criticism. As a result of this more intimate involvement in the daily pursuit of the war effort, more granular information about El Salvador must exist in U.S. files. Our government has a moral responsibility to release it to help families find healing.

To date, excerpts from the Yellow Book have been introduced as evidence in at least one case before the Salvadoran authorities. Brought by the daughter of disappeared parents profiled in the book, the case has advanced little in three years. But in a recent interview, she expressed optimism that the overturn of the Amnesty Law might mark the difference, not only in opening up the possibility of prosecution, but also in spurring conversations long silenced by fear. “Justice,” she said, “doesn’t only come to pass through the work of tribunals … it also comes to pass through recognition that this happened, it happened here, for these reasons … that recognition can come to constitute, for me, a form of reparation.”

As academic researchers — particularly those of us with access to well-resourced libraries that grant access to archives beyond the reach of most survivors in El Salvador — we, too, have a role to play in helping families heal.

Angelina Snodgrass Godoy serves as the Helen H. Jackson Chair in Human Rights and Director of the Center for Human Rights at the University of Washington in Seattle. Prior to pursuing her doctorate, she worked for human rights NGOs. She spoke for CLAS on October 7, 2016.