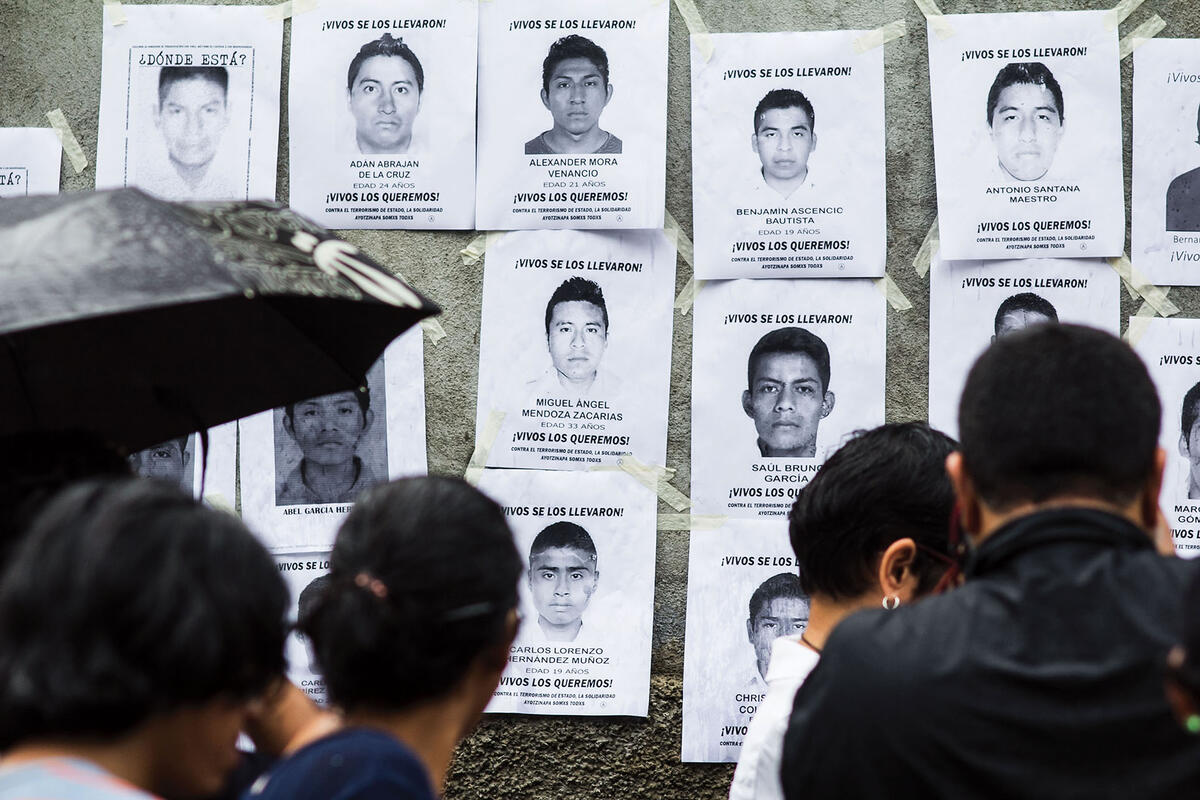

On September 27, 2014, in the early hours of the morning, 43 students from a rural teacher’s college were forcibly disappeared near Iguala, in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. More than two years later, their whereabouts are still unknown.

Their families continue to demand answers from President Enrique Peña Nieto’s government, whose legitimacy has been marred by its failure to adequately investigate the tragedy. Joining the families of the disappeared in their long fight for answers is Claudia Paz y Paz, a criminal law expert and human rights leader. Paz y Paz cut her teeth investigating mass atrocities as the first female non-interim attorney general in her home country of Guatemala.

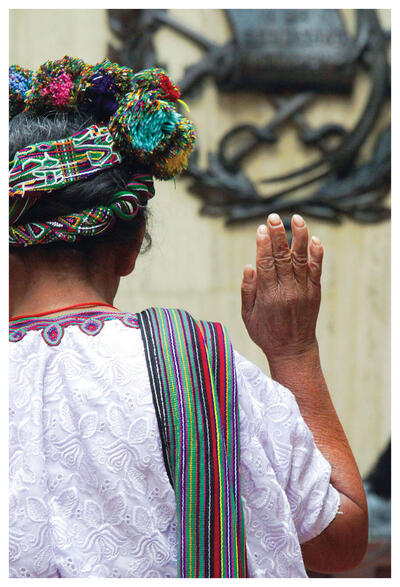

Taking a Stand in Guatemala

When Claudia Paz y Paz presented herself as a candidate for attorney general of Guatemala in 2010, the field of nearly 50 candidates included only six women. The criminal law expert added her name to the running not because she believed she had a chance of winning the appointment, but because she thought her solid credentials would force a substantive debate about the merits of the other candidates.

Much to her surprise, she advanced to the final round of six candidates. Then, President Álvaro Colom selected her as the first woman to serve in a non-interim position as Guatemala’s attorney general, the highest prosecutorial position in the country.

Paz y Paz had a choice to make. She could quietly occupy her position and avoid drawing the ire of the military and elite groups that have historically dominated Guatemala’s judicial system, or she could attempt to prosecute those responsible for killing 200,000 Mayans during Guatemala’s 30-year civil war, which ended with the signing of the 1996 Peace Accords.

To choose the latter would mean risking everything: her job, her political career, even her life. For her, the choice was easy.

The Ríos Montt trial launched Paz y Paz into the international spotlight as someone willing to seek justice even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds and great personal danger. As death threats poured in from those who saw their decades-long impunity suddenly endangered, so did the accolades, including a nomination for the 2013 Nobel Peace Prize. Paz y Paz shocked the country and the world when her prosecutorial team won an unprecedented conviction for genocide and other human rights abuses in the trial of former General Efraín Ríos Montt, who served as president during the bloodiest years of the civil war.

The genocide trial created political chaos at home. Guatemala’s Constitutional Court overturned Ríos Montt’s conviction on a technicality, then removed Paz y Paz from office six months prior to the end of her 2014 term.

She was not long idle. Tragedy in Mexico soon called for her precise skills and expertise.

Missing in Mexico

On the night of September 26, 2014, a group of students from a rural teacher’s college in Ayotzinapa, in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, traveled to the nearby city of Iguala to raise money and commandeer buses to help them travel to Mexico City, where they planned to commemorate the 1968 massacre of student protesters at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco. By early the next morning, 43 of those students were missing, 40 people were injured, and six people were dead.

The anguish of the students’ families caught fire across the nation, and tens of thousands of people demonstrated in Mexico City. The hashtag #FueElEstado (It Was the State) channeled anger towards the government. The official story pushed by representatives of the government was that Iguala’s corrupt mayor had handed the students over to a local drug trafficking gang to prevent them from causing disturbances in a political rally; then, the gang had killed them and burned their bodies in a local garbage dump. Yet, millions across Mexico refused to accept this story, demanding instead “que nos entreguen vivos a nuestros hijos” (give us back our sons alive!)

Creating the GIEI

With domestic investigations proving fruitless in locating the students and international pressure rising, the Mexican state entered into an agreement with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and representatives of the disappeared students to create the Grupo Interdisciplinario de Expertos Independientes (GIEI, Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts) in November 2014. Claudia Paz y Paz, recognized as one of the foremost human rights lawyers in the hemisphere, was invited to join the team, along with two Colombian lawyers, a Chilean lawyer, and a Spanish psychiatrist.

The GIEI had four mandates: to contribute to the investigation carried out by Mexico’s Office of the Attorney General; to accompany the search for the disappeared students; to review plans for reparations for the families; and to develop general recommendations surrounding the problem of forced disappearances in Mexico.

On October 20, 2016, six months after the GIEI published its second and final report detailing the results of its investigation, Paz y Paz spoke about her experience at the invitation of UC Berkeley’s Center for Latin American Studies.

Fact Finding

Paz y Paz first discussed the GIEI’s notable factual findings, many of which depart sharply from public statements offered by the Mexican government. The students did not visit Iguala to boycott a public talk given by the mayor’s wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda, whose family ties to drug trafficking organization are by now well known. In fact, the talk ended before the students arrived in the city. The students were not armed: recovered buses showed hundreds of bullet holes originating outside, but not a single shot fired from within. From the time the students were first intercepted at 9:30 p.m., they were subjected to increased violence over the course of five hours, in nine different locations, across 30 miles. Of the 180 direct victims of the night’s attack, 40 people were injured, 43 students were disappeared and remain missing, and six students were killed, their remains recovered. Implicated in the violence are the local police forces from Iguala and nearby Cocula as well as state and federal police and members of a municipal police force from Huitzuco. In addition, evidence showed the presence of federal military forces at several of the nine crime scenes.

The GIEI’s findings cast serious doubt on the government’s assertion that the students were killed by members of the Guerreros Unidos drug cartel, who allegedly burned their bodies in Cocula’s local garbage dump. That story, Paz y Paz noted, was supported only by the “confessions” of alleged members of Guerreros Unidos detained soon after the event. But medical reports reveal strong evidence that those detainees were tortured.

Furthermore, their confessions contradict one another and likewise go against the scientific evidence produced by the GIEI and Peruvian fire forensics expert Dr. José Torero, who works with the Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF, Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team). According to their findings, a fire of the size necessary to completely incinerate 43 bodies could not have occurred in the dump in the early morning of September 27. A blaze of that magnitude would scorch not only the entire dump, but also the surrounding trees. Indeed, no scorch marks were found, and the GIEI even discovered shrubbery growing inside of the dump that pre-dates the alleged fire in that location.

These details raise an important question: if the students were not abducted for political activism against the corrupt mayor’s wife, why were they greeted with such force by city, state, and federal police officers as well as the military? What threat could a group of unarmed students from a poor teacher’s college possibly pose?

Exploring Motives, Implicating the State

Paz y Paz explained a possible motive for the students’ disappearance. From surveillance video, the GIEI learned of the existence of a fifth bus that the students seized at the Iguala bus station, but was not included in the government’s investigation. When the GIEI asked the government about the fifth bus, they were presented with a bus with different markings from the one in the video. The possible implications of this fifth bus became clear when the GIEI learned of a federal criminal case in Chicago, Illinois, against members of Guerreros Unidos who moved heroin from Iguala to Chicago in commercial passenger buses not unlike those the students attempted to commandeer.

Did the students accidentally seize a bus loaded with heroin bound for the United States? In such a scenario, violence against them could have been an attempt to recover the merchandise. If the students did stumble unknowingly into a drug-running operation, the involvement of various levels of police and the military in violently attacking them implicate all levels of the government.

The GIEI further called the government and its investigation into question when it discovered interference with crime scenes. Divers from the Fuerza de la Infantaría (Mexico’s Marine Corps) claimed to find a bag of human remains in the San Juan River on October 29, 2014. The official explanation was that members of Guerreros Unidos dumped the incinerated remains of the students in the river.

However, videos and photos collected by local journalists show the director of Mexico’s Agencia de Investigación Criminal (Criminal Investigation Agency) present at the same spot on the river on October 28, accompanied by one of the alleged members of Guerreros Unidos who had “confessed” to killing and burning the students, but whose medical report revealed signs of serious torture while detained (notably, 30 lesions that occurred after his arrest). Photos also show members of the Attorney General’s Office manipulating evidence at the river on October 28. Though the GIEI called for an independent inquiry into the events of October 28, the investigation was kept internal, and its results have not been officially published.

Paz y Paz noted that during the last months of the GIEI’s mandate, their efforts were increasingly frustrated. The federal government repeatedly forbade them from interviewing soldiers who were present the night of the disappearances at several crime scenes. The justification for this refusal was sovereignty: soldiers need not speak to foreign investigators. The GIEI was prohibited from re-interviewing those Guerreros Unidos detainees who were tortured. Paz y Paz added that the government lost or destroyed important evidence, and several of the GIEI’s requests were postponed until their mandate expired and they were forced to leave the country.

Still Seeking Answers

With her participation in the GIEI, Paz y Paz demonstrated, once again, that she is not afraid to ask tough questions of those in power. Nonetheless, her presentation at UC Berkeley left open as many questions as it resolved. If the government’s assertion that the students were burned in the dump is not true, and if evidence indicates that the remains found in the river may have been planted there, what really happened to the students? Where are they?

If the students did indeed accidentally stumble onto a heroin-running operation, does this hypothesis justify or explain the sudden and violent loss of 43 lives or the agony of 43 sets of parents, thousands of community members, and millions mourning in the nation and around the world?

For Paz y Paz, the answer is no.

She lauds the courage and tenacity of the parents of the 43 students and notes that the GIEI was successful in clarifying certain facts and highlighting weaknesses and contradictions in the Mexican government’s official investigation, yet the story is not over. The students are still missing, and their mothers and fathers are still waiting for them. It is in their names that Paz y Paz urges us to keep demanding more from those in Mexico with the power to push the investigation further.

At a time when impunity and corruption highlight the failures of Mexico’s justice system, Paz y Paz and the work of the GIEI shine through as an example of extraordinary personal courage and a reminder of the importance of international collaboration in the protection and promotion of human rights. Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In this case, it is Claudia Paz y Paz doing the bending.

Claudia Paz y Paz, Guatemala’s first female Attorney General (2010–2014), is currently the Secretary of Multidimensional Security at the Organization of American States (OAS) in Washington, D.C. She spoke for CLAS on October 20, 2016.

Brittany Arsiniega is a Ph.D. student in Jurisprudence and Social Policy at UC Berkeley.