So much of North America’s history has focused on the differences between Mexico, the United States and Canada that few people on the continent realize how much they have in common. One leader who does is Vicente Fox Quesada, the first genuinely, freely elected president of modern Mexico. His grandfather was a gringo and an evangelical Christian who never learned Spanish but came to love Mexico and marry a devoutly Catholic Mexican woman. “My grandfather,” Fox told me, “galloped down from Ohio and found his American dream in Guanajuato.”

The stories of anti-Americanism in Mexico and Canada and of U.S. arrogance toward or ignorance of its neighbors are widespread and well-known. Nonetheless, I decided to look closely at public opinion surveys on North American relations in all three countries during the past 30 years. To my surprise, I found that Mexicans, Canadians and Americans like and trust each other and that their values are converging. Of course, there are moments when public opinion turns negative toward each neighbor — usually due to economic hardship, insults or unilateral actions, but on the whole, Fox was right. All three peoples share common dreams and actually want their governments to collaborate much more than our leaders do.

Fox tried to sell his inclusive vision of North America to U.S. President George W. Bush and Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien, but neither grasped it. However, two decades earlier, Ronald Reagan captured the essence of the North American vision when he said that “it is time we stopped thinking of our nearest neighbors as foreigners."

The Rise and Decline of North America

The Rise and Decline of North America

In the first seven years after the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) took effect in 1994, trade among the three countries of North America tripled, foreign direct investment quintupled, and North America’s share of the world product soared from 30 to 36 percent. During this time, 22 million new jobs were created in the United States.

Will Rogers once said that even if you are on the right road, if you sit down, you’re going to get run over. And that’s what happened to North America. We sat down in 2001, and China ran over us. Although Canada and Mexico remain the most important markets for U.S. goods, China has replaced them as the largest source of imports.

Since 2001, the growth in trade among the three neighbors declined by two-thirds; in foreign direct investment, by half; and the share of the world product sank to 29 percent. Intra-regional trade as a percent of the countries’ world trade rose from 40 percent in 1992 to 46 percent in 2001 and then fell back to 40 percent in 2009.

Besides China, what explains the decline? Additional reasons are new security barriers because of 9/11, the lack of investment in infrastructure, noncompliance with some Nafta provisions (e.g, trucking) and no continental strategy or institutions.

During the early period of integration, we began making products together — with parts of our cars crossing the borders many times before being fully assembled. The added cost of 9/11 restrictions transformed the North American advantage into a disadvantage, as China only had to surmount one border.

As integration advanced, many domestic issues — from drug-related violence to immigration, transportation, the environment and regulation — became transnational, meaning that we could no longer solve them without a new level of collaboration. Instead of rising to the new challenge, our leaders reverted to a traditional dual-bilateralism — dealing with one issue, one crisis, one country at a time. Progress was measured by the number of meetings rather than results. This strategy allowed Asia to acquire a new dynamic while the three countries of North America have slipped, blaming Nafta or each other for the problems that they share.

Recovering the Promise of North America

This is the moment to reinvigorate North America and forge a unique community of three sovereign states. In order to further develop the region’s economy and compete more effectively with Asia, North America should be more than a free-trade area. It should be a model of collaboration among nations at three levels of the international system. It should start with a vision based on three core principles:

Interdependence. The essence of a community is that each member has a stake in the success of the other, and all pay a price when one fails. When a neighbor’s house is vandalized, then all the houses in the community are in danger. When the value of a neighbor’s house rises, it lifts the value of the other homes. This means we need to address transnational challenges together and help each other to succeed

Reciprocity not unilateralism. Each nation should treat the others as it wants to be treated. The United States — because of its overwhelming power — has tended to insist on its way or the highway, or it can be courteous but unresponsive. Neither approach is appropriate in a community where each country should learn from and listen to the others and adjust its policies accordingly

A community of interests. Instead of seeking a quid for a quo, all three governments together should define shared problems and decide what each can contribute to solving them. If the paramount challenge in North America is to narrow the development gap with Mexico, all should decide what needs to be done to achieve that goal, and each should decide how it can contribute.

These basic principles — interdependence, reciprocity and community — seem obvious, and all three leaders often use the language and refer to their “shared responsibility,” but they rarely act on these principles. If the United States did, it would not permit 7,500 gun shops on the U.S. side of the border to sell assault weapons to the drug cartels. Instead of promoting “Buy American” or “Buy Canadian or Mexican,” all three would advertise “Buy North American” products.

Because the European Community became the European Union, some confuse the two terms and fear that a similar evolution might occur in North America. North America is not Europe, and it will not emulate the European Union. Indeed, the larger problem is that the desire to be different from Europe might lead policymakers to ignore the EU’s mistakes as well as its successes. The wise course would be to learn from Europe’s experience, avoiding the policies that failed and adapting those that succeeded.

A North American Community is decidedly not a North American Union, which is a unified state with a central government. Nor is it a Common Market where labor can move freely. At some point, the United States and Canada might permit their two peoples to move freely because the difference in the standard of living is not wide enough to generate a significant population shift. Of course, this is not the case with Mexico, and while some professionals, farm workers or unskilled laborers might be permitted freer movement, a Common Market is out of the question, until the income gap narrows significantly between Mexico and its northern neighbors.

The word “community” refers to a group in which the members feel an affinity and a desire to cooperate. It is especially appropriate for North America because it is flexible: it leaves space for all three countries to define it. It can be as limited or as expansive as its members choose, and it can change over time as the countries change and the region’s comparative advantage becomes clearer. Like the people and states of North America, the term “community” is eminently pragmatic. North Americans will choose their future based on their best judgment of what is likely to work.

A Blueprint

As the market enlarged to the size of the continent, the three countries of North America found themselves facing a domestic and continental agenda, while the institutions charged with dealing with the issues remained local or national. The immigration issue is shaped by people in small towns in Mexico in search of a better life; employers in the United States seeking reliable, hard-working and inexpensive labor; and other Americans worried about their jobs and culture. The trucking issue is driven by the U.S. Teamsters Union, but it also has consequences for Mexico and the credibility of the U.S. government. The “Buy American” issue is driven by America’s fear of the growing strength of China, but its most serious effect is on Canada and Mexico. What is needed is a comprehensive approach to the full gamut of continental issues organized around four broad goals: invigorating the North American economy; enhancing national and public security; addressing the new, transnational agenda; and designing effective tri-national institutions.

The Idea

The three governments have been working on most of these issues in a quiet, incremental way in two parallel groups. Occasionally, they will offer a declaration or an “action plan,” as they did in December 2011. The U.S.–Canadian and U.S.–Mexican Action Plans were similar and were checklists of studies they intended to do, not a summary of actions. Actual progress has been hard to discern. The problem is that special economic or bureaucratic interests oppose changes to the status quo, and there are few political incentives to overcome these groups. That is why the effort needs to begin with a “North American Idea,” the premise that a new relationship is essential to stimulate the economy, ensure greater security and define a model for the world.

It is unrealistic to expect these ideas to become policy in a short time. Big ideas take time for the body politic to absorb. When American women convened a meeting in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 to seek the right to vote, who would have thought it would take 71 years to succeed?

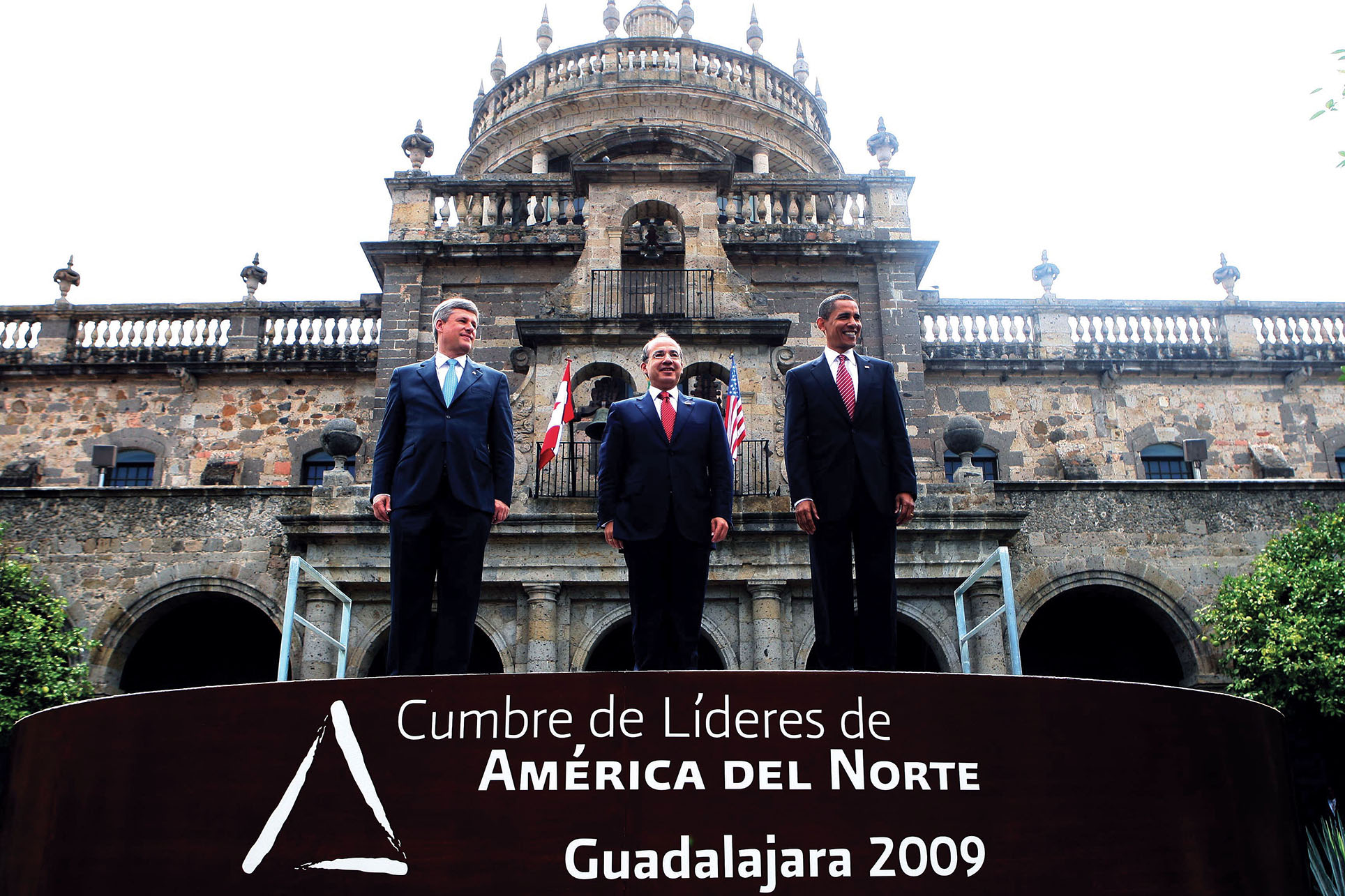

Still, this does not mean we should give up or slow our efforts. A compelling idea — like North America — and what it means for the people of all three countries could eventually mobilize a nation to overcome the forces arguing for the status quo. It will take time and leadership. It could start with representatives from the border regions because they have the largest stake in building a community. The two presidents and one prime minister could articulate the vision and educate their citizens. They could begin with a few, inexpensive initiatives, which nonetheless could raise consciousness. They could merge the two sets of parallel working groups on borders and regulations into a single North American group. They could ask their ministers of transportation to develop a North American Plan in a year. They could allocate just $15 million for scholarships and research centers for North America. This would be a good start.

Still, this does not mean we should give up or slow our efforts. A compelling idea — like North America — and what it means for the people of all three countries could eventually mobilize a nation to overcome the forces arguing for the status quo. It will take time and leadership. It could start with representatives from the border regions because they have the largest stake in building a community. The two presidents and one prime minister could articulate the vision and educate their citizens. They could begin with a few, inexpensive initiatives, which nonetheless could raise consciousness. They could merge the two sets of parallel working groups on borders and regulations into a single North American group. They could ask their ministers of transportation to develop a North American Plan in a year. They could allocate just $15 million for scholarships and research centers for North America. This would be a good start.

The 18 proposals I set forth (see box below) are all aimed at the three central challenges of North America — to narrow the development gap and to stimulate all three economies; to create lean, but innovative institutions to propose and monitor North American plans; and to foment a new style of global leadership for the world’s strongest power. None of the three challenges can be achieved by a single country, working on its own, and that is the real message of the North American Community. Mexico cannot lift itself from poverty without the help of its neighbors. Canada can design North American institutions, but it cannot implement them without the agreement of its neighbors. U.S. leadership depends on Canadian and Mexican cooperation and a new mechanism to organize the U.S. government so that it can address domestic issues with the Congress and its neighbors at the same time.

These challenges are not even on the agenda of the three governments. The reason is that the leaders have not begun to think continentally, and as long as they focus on bilateral relationships, they will be blind to the promise and the problems of the entire region. At base, today’s problems are the result of the three governments’ failure to govern the North American space. Once they visualize “North America” and decide to approach their problems from a continental perspective, solutions will appear that were previously invisible.

None of the many proposals that have been advanced for the region can be achieved without such a vision. Americans and Canadians will not provide funds to a North American Investment Fund to narrow the development gap with Mexico without a convincing vision of how Mexico’s growth will benefit their countries. There is little prospect of reaching an agreement on labor mobility, harmonizing environmental standards, forging a transportation plan or most any proposal that would cost money or change the status quo, unless there is a vision of a wider community that could attract the support of the people and their legislatures. A vision can inspire nations to redefine themselves and imagine a different future. “North America” could be that idea.

Robert A. Pastor is a professor of International Relations and the founder and director of the Center for North American Studies at American University. He is also the author of The North American Idea: A Vision of a Continental Future (Oxford University Press). He spoke for CLAS on September 19, 2011.

Pastor’s Blueprint for North America

To invigorate the North American economy, the three governments should:

- Create a North American Investment Fund to narrow the development gap by investing in infrastructure — roads, railroads, communications — to connect the poorest parts of Mexico to the thriving markets to the north.

- Design a North American plan for transportation and infrastructure that will reduce transaction costs, relieve congestion and promote trade and new links among all three countries.

- Conduct routine consultations among the key economic policy agencies — Treasury, the Central Bank, Budget — so that they can anticipate and coordinate rather than undermine one another’s economic policies.

- Negotiate a customs union with a common external tariff in order to eliminate costly “rules of origin.” That would remove an inefficient and exorbitant “rules of origin” tax on all North Americans, which was estimated to be as high as $510 billion in 2008, and the funds from the common tariff could be used for the North American Investment Fund.

- Promote regulatory convergence to improve environmental, health and labor standards on the continent without adding costs or unfairly protecting certain firms.

To enhance national and public security, the three governments should:

- Integrate their approaches to the drug problem as both a “health” and a law enforcement issue, ban the sales of assault weapons and tightly restrict the sales of weapons in border-area gun shops.

- Enhance interagency and international cooperation to manage the border more effectively and strengthen counter-terrorism without impeding legitimate travel and trade. This will require sharing intelligence, harmonizing visa and customs procedures and unifying “trusted traveler” programs with a single, jointly approved “North American passport.”

- Improve collaboration and response to natural disasters and pandemics.

- Reorganize the U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and integrate the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) so that it includes representatives from all three countries on behalf of a unified defense plan. Develop a common approach to assisting Central America and the Caribbean with counter-narcotics activities.

To address the new transnational agenda, the three governments should:

- Grant preferential access for immigrants from North American neighbors and pledge to treat all immigrants — whether legal or illegal — with fairness under the rule of law. Among the elements of a comprehensive plan for the United States are the following: stronger enforcement in the workplace with a biometric card to identify job applicants; a path to legalization for the 11 million people in the country without documents; a temporary worker program to be managed in accordance with the labor demands of the economy; acceptance of more immigrants with higher skills; and a program to narrow the income gap with Mexico.

- Adopt a formula that balances the region’s interest in energy security with the necessity of curbing carbon emissions. Such a formula has eluded each nation working on its own; perhaps it would be easier for the groups within each state to accept if all three countries agreed.

- Seek a social charter that would identify the rights of workers in each country, set North American standards and adopt a plan of action for achieving those rights.

- Modify textbooks to include a section on North America and more on the other two countries, provide scholarships for studying in universities in the other two countries and fund research centers on North America.

To design lean but effective tri-national institutions, the three governments should:

- Hold annual summit meetings.

- Establish an independent North American Advisory Council composed of a diverse group of leaders from all three countries with a research capacity and a mandate to propose North American initiatives in every area for the summit meetings.

- Merge the U.S.–Mexican and the U.S.–Canadian Parliamentary Groups into a North American Parliamentary Group to help the three legislatures understand the tri-national dimension of the issues and forge common approaches.

- Strengthen existing Nafta institutions like the North American Free Trade Commission, the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), the Commission for Labor Cooperation and the North American Development Bank.

- Create new North American institutions, notably a Permanent Tribunal for Trade and Investment, a North American Competition Commission and a North American Regulatory Commission.