Argentina’s economy is in trouble. The Argentine peso saw a 90-percent devaluation from April 2018 to September 2018. Inflation rates are projected to be 30 to 40 percent in 2018 and what was seen as a potential growth year is now forecast to see a 1-percent contraction of its GDP. The country’s economy is at its most fragile since the 2001-2002 economic crisis, and many Argentineans face the possibility of poverty as the country tries to find a way out of its economic woes.

During her talk fo the Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) in September 2018, Alison Post, Associate Professor of Political Science and Global Metropolitan Studies at UC Berkeley, discussed how worsening external conditions have complicated efforts by Argentina’s current president, Mauricio Macri, to reverse the troubled fiscal situation he and his Cambiemos coalition inherited when they came to power in late 2015. Argentina’s problems are related to a variety of economic and political factors, but broad-based consumer subsidy programs have played a crucial role in how the crisis has unfolded, argued Post.

President Mauricio Macri and his political allies won the 2015 elections based on a campaign platform stressing the need for economic reform. When Macri assumed office, the inflation rate was about 27 percent, the budget deficit had grown to 7.1 percent of the GDP, and the government spent the equivalent of approximately 5 percent of the GDP on subsidizing consumer prices for privatized public services such as electricity and natural gas. Rather than implementing sudden and large cuts to government expenditures reminiscent of the structural adjustment programs adopted in preceding decades, President Macri pursued a “gradual” approach to economic reform.

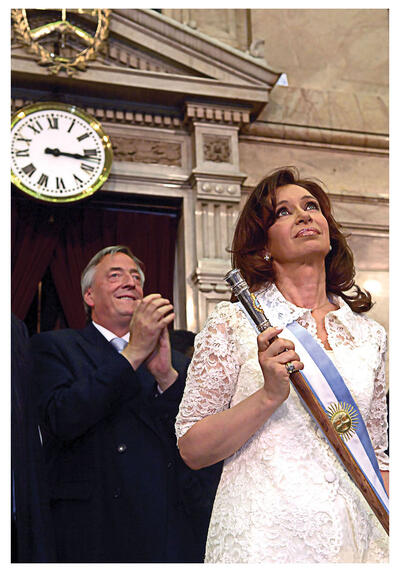

First, his administration removed the limit on the number of pesos an individual could exchange for dollars — known as the cepo al dólar — which had led to the emergence of a black market for U.S. dollars. Removing the “cepo” caused the Argentine peso to depreciate from 10 to 15 pesos to the dollar. Second, Macri reached an agreement with holdout creditors who had not entered the prior agreement, and thus, Argentina regained access to international credit markets. The government subsequently contracted debt, much of which was in new foreign currency, to finance the existing budget deficit. Third, the government created a new inflation measure to return credibility to government statistics, which under the administrations of Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2015) had come to diverge significantly from private estimates. Fourth, gradual cuts were made to consumer subsidies for privately provided public services, namely electricity, gas, and public transportation. Fifth, taxes on agricultural exports were reduced in order to incentivize production and trade.

In taking this gradual approach to economic reform, Macri and his team ran a major risk: they assumed that the United States and other international entities would avoid quickly increasing interest rates, which would have made it harder for Argentina to continue financing budget deficits. This approach was successful as late as 2017, when the economy showed signs of improvement. Although inflation increased in 2016 — in part due to the subsidy cuts, which forced consumers to pay more — the economy grew 3 percent, and inflation decreased in 2017.

Argentina’s economic situation began to deteriorate towards the end of December 2017, as the United States and the European Union engaged in macroeconomic tightening. Combined with rising oil costs, the U.S.–China trade war, a drought that devastated key agricultural exports, and a major corruption scandal implicating the prior administration, Argentina’s economy took a turn for the worse. The government’s August 2018 announcement that it had requested an advance disbursement of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan rattled markets — investors were reminded of the 2001 crisis.

How has the government responded to the worsening economic situation? To stem capital flight, the country’s central bank, the Banco Central de la República de Argentina, raised its overnight lending rate to 60 percent, the highest in the world. And the government has been negotiating the terms under which the IMF will release a US$57.1 billion loan approved towards the end of September 2018. The IMF has asked the government to accelerate its deficit-reduction program, bringing it to zero percent from the previously planned 1.3 percent of the GDP deficit. To accomplish this reduction, the administration is negotiating with provincial governors, as a large portion of government expenditure occurs at the subnational level. The administration and the governors have tentatively agreed to pairing expenditure cuts of approximately 1.4 percent of the GDP with revenue increases of approximately 1.3 percent of GDP (from the agricultural sector). Cuts are to be spread among investments in public works, utility subsidies, operating expenditures for the state, and public-sector hiring freezes.

Implementing cuts to subsidies that reduce consumer prices for services such as gas, electricity, and public transit will be complicated. The devaluation of the Argentine peso and continuing inflation has had an impact on the financial situation of the utilities that are required to sell services at regulated prices. In the case of natural gas, for example, the massive devaluation has created pressures for subsidy growth because much gas is imported, and subsidies cover the difference between international and domestic prices. Neither industrial nor residential consumers are well placed to absorb mounting prices as the economy deteriorates. Macri faces a dilemma: continue cutting subsidies to comply with IMF requirements to reduce the fiscal deficit or tame subsidy reduction and jeopardize the agreement with the IMF.

Consumer Subsidies and the Current Crisis

The above account highlights the central role played by consumer subsidies in Argentina’s current economic situation. Argentina is not unique in devoting a large fraction of the government budget to consumer subsidies, however. Many developing countries devote significant resources to lower consumer prices for basic goods and services like food and electricity. These expenditures often exceed what is spent on basic health and education

Many factors contributed to this decision. The first were price pressures. Inflation and increases in the price of imported inputs — such as natural gas — resulted in increases in the fiscal burden imposed by consumer subsidy programs. For example, shortages in domestically produced gas led the Kirchners to create a new state-owned petroleum and natural gas company, Energía Argentina Sociedad Anónima (ENARSA), which subsidized the difference between international prices and the frozen price of gas on the domestic market. The government-mandated frozen rates were thus viable for consumers. When the price of imported gas tripled, however, the costs of these subsidies automatically grew, especially as domestic supply shortages became more pronounced. Argentina’s current consumer subsidy program dates back to the 2001-2002 financial and political crisis. Following the peso’s devaluation, President Eduardo Duhalde (2002-2003) chose to freeze the rates charged by privatized utilities, given the large income shock experienced by the population. Presidents Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner maintained utility rate freezes and related subsidy programs to mitigate price fluctuations through their respective administrations from 2003 through 2015, even as the economy recovered. Over time, the fiscal burden of the consumer subsidy program grew dramatically. By 2010, the government devoted about $30 billion pesos or approximately 10 percent of government expenditure to utility subsidies. Professor Alison Post and Tomás Bril Mascarenhas, UC Berkeley Ph.D. alumnus and now Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and Government at the Universidad Nacional de San Martín in Argentina, address this issue in a co-authored article entitled “Policy Traps: Consumer Subsidies in Post-Crisis Argentina.” They argue that “developing countries tend to adopt and subsequently increase outlays for broad-based consumer subsidy programs when the price of key inputs — such as imported fuel or domestic labor — rise rapidly. In absence of these programs, price increases would trigger increased living costs for many citizens. These initially modest consumer subsidy programs come to form ‘policy traps’ that limit a politician’s ability to alter or remove them.”

In the case of subsidies for bus tickets, the price pressure came from inflation, which increased labor costs. After receding in 2002, inflation rose to double-digit levels in 2004, and then exceeded 20 percent in 2008 and 2010. Workers demanded wage increases and managed to extract a 90-percent real wage increase between 2003 and 2010. At that point, wages constituted 50 percent of operation costs. Officials chose to subsidize the gap, rather than risk angering the public through price hikes for bus tickets.

Concerned about maintaining their hold on power in the short run, the Kirchners chose not to repeal or reduce subsidies. Consumer prices were held constant at pre-crisis levels, even as inflation and rising input costs increased the fiscal burden of the government’s subsidies to maintain these prices. The Kirchners had many disincentives to repeal, chief among them, subsidy beneficiaries were concentrated in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Region, the site of the controlled bus/transit services and major gas networks. Neither Kirchner administration wanted to run the political risk of turning public opinion against them in such an influential urban center.

In fact, public opinion in 2006 stood firmly behind the rate freezes. Protests in the provincial capitals, where subsidies were scaled back, reminded the Kirchners of the potential for — and visibility of — public protests against price increases. Tentative efforts to curtail gas subsidies in 2008 generated such strong reactions that the Kirchners refrained from any attempt to modify them for three years. By 2010, if subsidies for buses were eliminated, prices would need to rise by 300 percent to cover costs. The gap between “real” and subsidized prices grew over time, as did the political costs of repealing the subsidies. When Macri arrived in 2015, he vowed to eliminate these subsidies, yet three years later, they still remain. Why? Consumer subsidies not only comprise half the deficit but distort incentives for residents to conserve energy. Those living in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Region pay 10 times less for electricity than residents of other urban areas in the neighboring countries of Brazil and Uruguay.

Macri took a gradual approach to reducing subsidies, and he and his team encountered more roadblocks than they expected. For example, the current administration started phasing out subsidies to wholesale power distributors in 2016. In June 2016, the government moved on to natural gas, but limited changes to large industries when households and small businesses showed signs of discontent. The nation’s Supreme Court further delayed gas hikes when it ruled that the administration needed to hold public hearings. In January 2017, the government announced new energy guidelines phasing out consumer subsidies for electricity by 2019. Exchange rate pressures and concerns about stoking inflation and voter backlash continue to constrain efforts to wind down this subsidy program.

Environmental factors will make eliminating subsidies difficult as inflation increases, the Argentine economy remains weak, and public resistance grows against the emerging austerity program. IMF pressures to reduce the budget deficit and the severity of the country’s financial situation, however, may force the Macri administration to make at least partial reductions.

The president’s core constituents, in Buenos Aires province and the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Region, will shoulder the bulk of price increases. At the same time, these populations may be the most likely to understand why the era of subsidized utility prices is over.

The Future of Argentina’s Economy — and of President Macri

Argentina needs to break the vicious cycle characterized by unsustainable budget deficits, decreasing investor confidence, and growing political paralysis. Some analysts have advocated for immediate, full-scale reform including: adopting new labor reforms to lower public expenditures; reducing public sector employment; cutting utility subsidies (which would disproportionately affect Buenos Aires province and the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Region); incentivizing provinces to rein in expenditures; and making social programs more targeted. Others argue that such a dramatic decrease in government spending could push Argentina’s economy further into recession, as occurred in Greece.

As for President Macri’s future, it’s too soon to tell, as the situation in Argentina changes day to day. Post looks to an analysis by Maria Victoria Murillo, Professor of Political Science and International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, who suggests that Macri will likely serve out his term but may not win re-election in 2019.

Many factors make it unlikely that Argentina’s president will resign or be removed from office. First, President Macri consolidated his political position in the 2017 midterm elections, whereas previous leaders who faced similar crises, namely Presidents Raúl Alfonsín (1983-1989) and Fernando de la Rúa (1999-2001), fared poorly and lost their popular legitimacy. De la Rúa’s Alianza had also lost its coalition partner by the time the crisis hit. In contrast, the Cambiemos coalition is still intact. Second, the Peronist party remains divided between progressives led by former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and moderates led by Sergio Massa. A more organized popular sector and heightened polarization will make it difficult to reach any agreement.

At the conclusion of Post’s presentation, questions from the audience highlighted the depth and historical roots of this polarization, which originates in the country’s controversial legacy of Peronism. Compromise will be necessary, however, for Argentina to avoid financial ruin. Whatever the case, 2018 may well prove crucial for Argentina and President Macri.

Alison Post is Associate Professor of Political Science and Global Metropolitan Studies at UC Berkeley. She spoke for CLAS on September 13, 2018.

Adan Martinez is a Ph.D. student in the Charles & Louise Travers Department of Political Science at UC Berkeley.