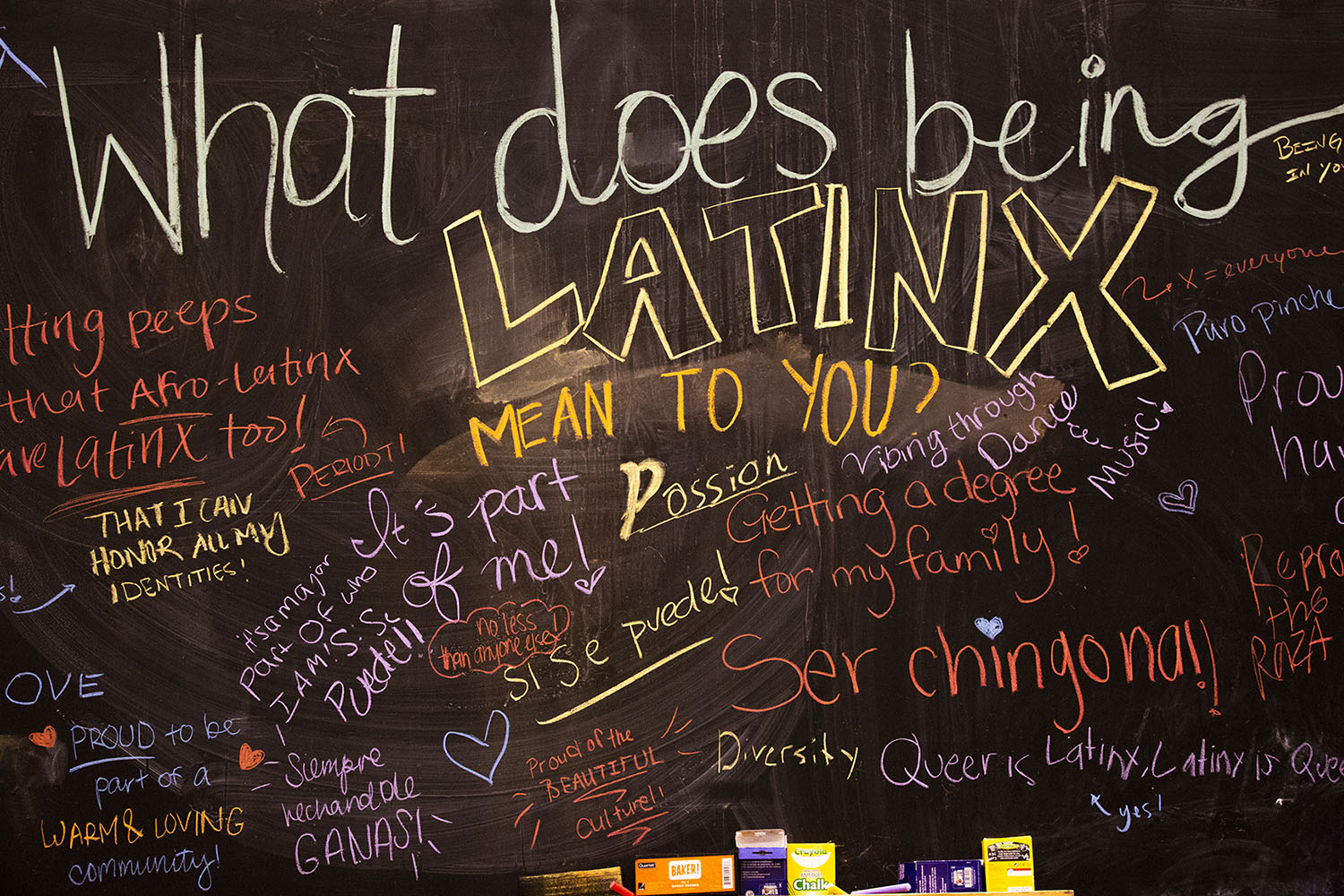

I saw the word latinx for the first time on flyers advertising community events at the Multicultural Community Center in 2016. I was an undergrad at the University of California, Berkeley, and working as a barista in the Martin Luther King Jr. Student Union. From that moment on, I began to see the word all around me. Cable news networks started using the term to designate voting populations. It appeared in communications from campus officials and more and more frequently on the Internet, especially social media.

In this fortuitous encounter with the word latinx, I discovered my primary research interests in linguistics, which was my intended area of study at UC Berkeley. As a student of Spanish (and being queer myself), I immediately knew what the word was supposed to mean. Spanish is a masculine–feminine gender language: all nouns—including those that refer to people—are grammatically either masculine or feminine. This gender is often marked with the suffix -o if the word is masculine (e.g., latino), or with the suffix -a if the word is feminine (e.g., latina). Use of the -x ending (e.g., latinx) represents the rejection of a binary gender marker. The -x crosses out gender marking in the language and provides a neutral alternative inclusive of nonbinary people. Throughout my undergraduate coursework, I hoped to see the topic of gender in language discussed but never did. My only frame of reference was my nonbinary Spanish-speaking friends, who were grappling with the issue of how to self-identify in a highly gendered language.

Inspired by these experiences, I set out to research the topic in my final year as an undergraduate, and I learned that “linguistic gender” meant something very different in linguistic theory than it meant in society.

In linguistics, the term “gender” usually refers to a particular feature of language called “nominal classification” (Corbett, 1991). In languages with a system of nominal classification, all nouns are assigned to one of two or more different classes, called “genders.” These genders often have nothing at all to do with social gender, as in the case of many African languages that have genders for plants and animals, among other things (Maho, 1999, p. 51). But in languages like Spanish, they have everything to do with social gender, though this particular relationship between grammatical and social gender is woefully under-described and sometimes even disputed.

I found that participants did not use traditional masculine or feminine forms to refer to this nonbinary subject, but instead, they used innovative forms, including nonbinary personal pronouns (elle, ellx, elli) and nonbinary grammatical genders (-e, -x, -i), or they tried to avoid any form of reference establishing gender whatsoever. In doing so, they proved that these genders were not capable of representing nonbinary people and that other gender categories in the language must be created for different communities of queer Spanish speakers.In order to better understand the role of social gender in Spanish grammar, I designed a pilot experiment that became the basis of my undergraduate thesis (Papadopoulos, 2019). In this experiment, I presented 11 native Spanish speakers (most of whom were queer, trans, or nonbinary) with a piece of clip art illustrating a nondescript person and the letters M and F crossed out, meant to signify the concept of “no masculino, no femenino” (neither masculine, nor feminine). I asked questions in English such as “How would you say this person is tall and blonde?” in order to discern how participants varied in their use of Spanish pronouns and gender morphology.

I found that participants did not use traditional masculine or feminine forms to refer to this nonbinary subject, but instead, they used innovative forms, including nonbinary personal pronouns (elle, ellx, elli) and nonbinary grammatical genders (-e, -x, -i), or they tried to avoid any form of reference establishing gender whatsoever. In doing so, they proved that these genders were not capable of representing nonbinary people and that other gender categories in the language must be created for different communities of queer Spanish speakers.In order to better understand the role of social gender in Spanish grammar, I designed a pilot experiment that became the basis of my undergraduate thesis (Papadopoulos, 2019). In this experiment, I presented 11 native Spanish speakers (most of whom were queer, trans, or nonbinary) with a piece of clip art illustrating a nondescript person and the letters M and F crossed out, meant to signify the concept of “no masculino, no femenino” (neither masculine, nor feminine). I asked questions in English such as “How would you say this person is tall and blonde?” in order to discern how participants varied in their use of Spanish pronouns and gender morphology.

My preliminary attempt to contextualize the concept of gender-inclusive language circulated among different scholar and activist circles after it was published online. Today, I continue this line of research as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley. As I have delved more deeply into the theory of linguistic gender in my graduate studies, I have found that current definitions are both too broad and too narrow. They are too broad in the sense that any language whose grammar is structured in the particular way described by the theory is identified as “having gender,” even if its systems have nothing to do with gender, and they are too narrow in the sense that all languages whose grammars are not structured in this particular way are identified as “genderless,” even if they manifest social gender distinctions in other ways. This includes “genderless” languages like English in which the concept of gender-inclusive language activism has largely originated. Current definitions of linguistic gender do not focus on the concept of social gender at all, and consequently, they describe a great number of languages as “genderless” when, indeed, they have features based on social gender.

Much of my graduate research interrogates this body of work in order to build toward a theory of gender in language that is based on the concept of social gender. Such a theory would identify the ways that masculine–feminine distinctions are encoded into the grammar and lexicon cross-linguistically, and it would isolate everything currently considered a feature of linguistic gender that, in reality, has nothing to do with social gender. It would also directly respond to attacks on gender-inclusive language by academies like the Real Academia Española and the Académie Française. These institutions claim that masculine and feminine grammatical genders are an arbitrary feature of language and that they can, in fact, represent nonbinary people; they reject gender-inclusive forms as not only unnecessary, but also a threat to the purity of the language (Real Academia Española, 2020; Académie Française, 2017). In part because of these attitudes, gender-inclusive forms are not officially approved for use in most Spanish- or French-speaking institutional contexts, including governments and schools, and they are stigmatized in society as nonstandard. In this way, empirically defining the interconnection of linguistic and social gender and proclaiming the legitimacy of gender-inclusive language could be of material benefit to queer, trans, nonbinary, and other gender-nonconforming people.

For me, building toward a new theory of gender in language has meant studying languages considered both gendered and genderless in order to investigate the ways in which they both conform to and challenge current definitions of linguistic gender. Two years after my original experiment, I revisited my work on gender in Spanish and completed another round of experimentation, this time with 20 Spanish speakers (half the subjects were native speakers, the other half were learning Spanish as a second language), examining where these speakers identified gendered distinctions throughout the language (Papadopoulos, in press-b). I showed participants a series of passages that I had written containing normatively masculine- and feminine-gendered content and asked them to transform these passages to become gender-inclusive where they referred to people. The design of the experiment intended to discern how participants of different language backgrounds reacted to content of different semantic and morphological types. I wanted to collect data exploring how part of speech (i.e., whether a given word was a noun, pronoun, adjective, or article) and other morphological properties (e.g., what gender morphemes appeared on the word, whether or not the word had forms in multiple genders) affected participants’ rates of gender-inclusive transformation.

This study had two main findings. First, all participants were more likely to transform content that referred to people than they were to transform content that did not refer to people, though to differing degrees based on their language backgrounds and the linguistic properties of individual words. Second, as in the pilot experiment, participants did not view masculine and feminine grammatical genders to be representative of nonbinary people. In order to express nonbinary gender identities, participants employed solutions proposed by gender-inclusive language activists (e.g., -e, -x, elle) with a high degree of regularity, seemingly introducing new grammatical genders. These results captured participants’ systematic deployment of gender-inclusive Spanish and described which types of words were the usual targets of gender-inclusive transformation.

In January 2021, seeking to move beyond Spanish, I began work on the Gender in Language Project (genderinlanguage.com). The first goal of the project is to write documents for as many language varieties as possible that describe the realization of normative masculine and feminine gender throughout the grammar and lexicon, also describing any innovative gender-inclusive forms that have been proposed or attested in each language. A related goal is to use these documents to produce pedagogical materials for different audiences (e.g., queer community members, educators, language instructors, students), explaining how to attend to gender in each language, how to use gender-inclusive forms, and how to teach about gender in the language classroom, among other topics. Most of all, the project is meant to be an open-access queer community resource and a knowledge project bound by an empirical research agenda.

I use the Gender in Language Project to mentor undergraduate researchers in the Departments of Linguistics and Spanish and Portuguese at UC Berkeley. These students are given a language based on their own language background and/or research interests and tasked with writing the language’s documents. I teach them to how read prescriptive grammars, journal articles, and other empirical sources for features of gender in different languages and then to find community-level resources (e.g., tweets, blog posts, community grammars) describing proposals and/or attestations of gender-inclusive forms in the language.

With this data, we are able to describe the realization of prescriptive masculine and feminine genders and, where applicable, extrapolate patterns in the realization of inclusive gender(s) in each language. Apart from undergraduate researchers at UC Berkeley, the project also receives support from other researchers working on the concept of gender inclusivity in different languages, including community members, undergraduate and graduate students, and faculty at different institutions around the world.

The first version of the Gender in Language Project launched quietly in May 2021, after a semester in development with a team of six undergraduate researchers plus myself. Using empirical and community-generated sources, as well as data from my most recent experiment, we wrote a grammar of Spanish, describing the realization of masculine, feminine, and inclusive genders (e.g., -e, -x, -*, -i) throughout the language. We also created documents for Mandarin Chinese that identify masculine and feminine gender throughout the language—including in gender-marked radicals (components of Chinese characters)—and describe different nonbinary pronouns that have been proposed.

The second version of the Gender in Language Project launched in June 2022, this time with an expanded team of 12 undergraduate researchers and contributions from researchers at universities in the United States, Denmark, Russia, and Cuba. The second version introduces language documents for English, Danish, Portuguese, Catalan, Irish, Tagalog, Korean, and Vietnamese. With the data we have generated in just a year’s time, we have identified four features of linguistic gender that are not unified by current definitions. The first publication resulting from the Gender in Language Project argues the importance of a new theory of gender in language, using our data to explain how current definitions of linguistic gender fail to describe all gender-marked features of language cross-linguistically (Papadopoulos, in press-a).

Later in 2022, after describing a number of additional languages that have produced gender-inclusive forms (e.g., Hebrew, French) and soliciting feedback on our materials, the Gender in Language Project will be distributed widely to departments at national and international universities, as well as to national and international queer community organizations.

I have a number of future goals for the project. Besides contributing to empirical research on gender in language, it is my hope that the project will become an instrumental resource for community education, including within family and chosen family units, and that it will sensitize communities around the world to the experiences of nonbinary people. Practically speaking, I hope that the project receives support so we may continue our research and build a multilingual and accessible online environment.

I am so proud of how much we have achieved with the Gender in Language Project in a little more than a year, and I hope to continue to expand this vital line of research for many years to come.

The Gender in Language Project may be viewed at genderinlanguage.com.

Ben Papadopoulos (he or they) is a Ph.D. student of sociolinguistics in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at UC Berkeley and the founder and editor-in-chief of the Gender in Language Project.

Deborah Meacham is the editor of the Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies.

https://www.genderinlanguage.com/

https://www.genderinlanguage.com/

References

Académie Française. (2017). Déclaration de l’Académie française sur l’écriture dite “inclusive.” http://www.academie-francaise.fr/actualites/declaration-de-lacademie-francaise-sur-lecriture-dite-inclusive.

Corbett, G. G. (1991). Gender. Cambridge University Press.

Maho, J. F. (1999). A comparative study of Bantu noun classes (P-00404924) [Doctoral dissertation, Göteborg University]. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Papadopoulos, B. (2019). Morphological gender innovations in Spanish of genderqueer speakers/Innovaciones al género morfológico en el español de hablantes genderqueer [Bachelor’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley]. University of California eScholarship.

Papadopoulos, B. (in press-a). The definitional dilemma of gender in language. Hesperia: Anuario de Filología Hispánica.

Papadopoulos, B. (in press-b). Where does gender exist in gendered languages? Gender-inclusivity and the transformation of Spanish grammar. In E. L. Russell & K. Knisley (Eds.), Redoing linguistic worlds. Multilingual Matters.

Real Academia Española. (2020). Informe de la Real Academia Española sobre el lenguaje inclusivo y cuestiones conexas. https://www.rae.es/sites/default/files/Informe_lenguaje_inclusivo.pdf