Human rights organizations in Latin America have had much to celebrate in recent decades. The “justice cascade” forced the retreat of brutal regimes in the Southern Cone and Central America, with many authoritarian leaders losing their immunity and facing trial and jail terms. Human rights campaigns saved lives, freed prisoners, improved jail conditions, and aided in the demise of numerous military dictatorships. Some scholars and activists, however, have questioned whether the global human rights movement focused too much on preventing the state from committing heinous deeds and overlooked growing global inequalities. According to this view, human rights organizations shed light on, limited, and even prosecuted brutal imprisonments or forced disappearances (negative human rights, what the state cannot or should not do to individuals) but failed to pay sufficient attention to the accumulation of wealth and power among the top 1 percent. Critics, such as law and history professor Sam Moyn, recognize the achievements but highlight dire inequalities across the globe.

The debate resonates loudly in Latin America. On the one hand, local, national, and international organizations can take great pride in the impact of their denunciations of the brutality of U.S.-supported military regimes. In the 21st century, groups have prosecuted Augusto Pinochet, Jorge Videla, Alberto Fujimori, Efraín Rios-Montt, and other tyrants. On the other hand, Latin America has some of the world’s most profound inequalities, evident in income disparities and difficult access to basic services. These brutal socioeconomic differences, painfully underscored by the Covid-19 pandemic, endanger democracy and undermine the real achievement of human rights advances.

Such disagreement over the limitations of the human rights communities’ achievements can telescope their development in Latin America. The justice cascade stressed criminal hearings against human rights abusers rather than social justice and egalitarianism, but protecting the innocent and eventually prosecuting the guilty has not been the sole focus of decades of human rights work in Latin America. Many veterans in the human rights community contend that the struggles against injustice and the debates about its causes never ceased. The relationship between defending human rights and fighting for social justice needs to be scrutinized. Peru is a fascinating and insightful case to explore these issues.

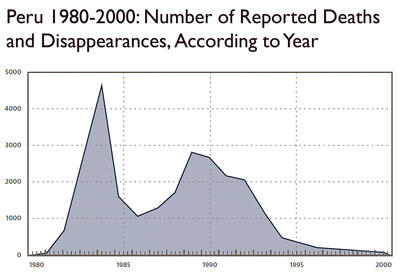

Peru confronted a horrific human rights debacle from 1980 to 1992, when the country was immersed in an “internal armed conflict” with the Maoist guerrilla group, Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path). The war with the Shining Path led to 70,000 dead, more than half of them at the hands of the guerrillas. Reacting to this bloodshed, national human rights groups multiplied in size and number, documenting and denouncing the situation. Did they ignore or abandon the critique of structural inequalities as atrocities increased and authoritarianism expanded? Were they slow to react to the horrors of the Shining Path? These questions can only be answered through an analysis of the human rights groups’ development, the obstacles they faced, and their achievements and limitations.

Born in the Struggle

In 1975, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez deposed General Juan Velasco Alvarado, the left-leaning leader of the first phase of the Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces. Morales Bermúdez imposed severe socioeconomic measures that eliminated most price controls, defunded social services, and criminalized strikes. If Velasco had sought to give power to the people, Morales Bermúdez seized it back. Broad sections of society opposed his authoritarian project, culminating in a massive national strike that shut down most of the country on July 19, 1977. The government acted with force. Hundreds of civilians were injured in protests and thousands detained, with as many as 5,000 union leaders fired. At this point, in 1977 and 1978, grassroots organizations began to use the language and tools of human rights to pressure the Morales Bermúdez regime and to defend those who were wounded, imprisoned, or fired.The Shining Path began its war in May 1980, burning ballot boxes in the tiny Andean town of Chuschi. A small Maoist party rooted in the Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga in the city of Ayacucho, the Shining Path contrasted with other Latin American insurgencies. They did not seek a broad revolutionary alliance, but instead perceived others on the left and members of grassroots organizations to be part of the enemy, the old order that needed to be eliminated. Within a few years, they had not only attacked the Peruvian state and military, but threatened and even executed anyone else who might question their Maoist project, from NGO workers to Catholic priests. The violence was fierce and shocking; the state reacted with brutality, as well. Nonetheless, human rights organizations did not emerge out of the bloodshed of the early 1980s. Instead, they grew out of the struggles against the Morales Bermúdez military regime (1975-1980). In this regard, they follow the pattern of much of Latin America.

These Comités de Derechos Humanos (Human Rights Committees) sprouted from the multiple and diverse leftist parties and organizations that had collaborated in the July 1977 strike and sought to organize the working class and the poor. The progressive Catholic Church constituted the other essential piece of the foundation. Peru was the birthplace of Liberation Theology, and since the profound doctrinal changes of Vatican II (1962-1965), many nuns, priests, and other members of the Church had dedicated themselves to working in poorer neighborhoods in cities and in the countryside. The Comisión Episcopal de Acción Social (CEAS, Episcopal Commission for Social Action) defended those involved in the protests of the late 1970s and promoted the work of local human rights groups. Although these early groups varied in objectives and methods, they shared a contempt for the Morales Bermúdez regime and a commitment to social justice. The 1978-1979 Constituent Assembly introduced derechos humanos as part of the political agenda. Peru’s human rights community dates from this period, firmly rooted in the left and among progressive Catholics.

Peru returned to democracy in 1980 with the election of Fernando Belaúnde Terry. Having received nearly one-third of the vote in the 1978 Constitutional Assembly, the left made periodic efforts to unite for electoral coalitions but was just as frequently divided. Some groups believed that elections and Congress held the key to their struggle, while others continued to focus on grassroots and worker organizations. Many still envisioned a revolution. But the emergence of the Shining Path and the incompetent and brutal reaction by the Peruvian state altered the situation. Human rights groups rapidly learned that the Shining Path was unique, a very different entity than the “new left” that had grown throughout the Americas since the 1960s. The guerrilla fighters did not use uniforms, respect civilians, or follow the Geneva Convention. Moreover, deeming anyone not a part of their Maoist project an enemy, the Shining Path attacked community leaders, labor organizers, and eventually, human rights advocates. The police and then the military reacted to the guerrillas with violence and little respect for international norms, yet the armed forces consistently rejected the denunciations of their own atrocities. The nascent human rights community found itself caught between two fires, attacked by both the Shining Path and the state. This situation would only worsen.

In December 1982, President Belaúnde declared a state of emergency in Ayacucho and sent in the military. At this point, human rights abuses escalated. Torture, disappearances, and massacres became commonplace. While the military used brutal counterinsurgency tactics, the Shining Path imposed its will through coercion. The infamous massacres of the mid-1980s encapsulate these horrors: in April 1983, the Shining Path killed 69 people in Lucanamarca; in December 1984, the military killed 123 in Putis. All the victims were Indigenous peasants. These are just two examples — there were many more.

As the body count increased, human rights groups likewise grew in size and number. International organizations such as Amnesty International (1981) and the Comisión Andina de Juristas (Andean Commission of Jurists, 1982) set up offices in Peru. National organizations also formed in the early 1980s, including the Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos (APRODEH, Association for Human Rights), the Instituto de Defensa Legal (Legal Defense Institute), and the Asociación Nacional de Familiares de Secuestrados, Detenidos y Desaparecidos del Perú (ANFASEP, National Association of Family Members of the Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared of Peru). In 1985, dozens of groups created an umbrella organization, the Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDDHH, National Coordinator for Human Rights).

Human rights groups understood that they needed to collaborate and operate nationally, maintaining a presence in the “emergency zones,” where the conflict was most dire, despite the obstacles and dangers. They received support from international organizations — technical and financial help as well as solidarity — and learned from the experiences of other countries. One activist described it as a “crash course in human rights.” The escalating violence only made their task more urgent and more difficult.

From the outset, human rights groups faced opposition. Some on the left dismissed them as bourgeois, as too focused on the individual over the collective. Nonetheless, all of the leaders I spoke with insisted that once the seriousness of the situation became clear — the body count rose, and news stories about massacres finally reached a broad audience — support for their work increased, not only from the left, but from the center and even some conservatives. The Shining Path and the Peruvian military, however, criticized the notion of human rights and its practitioners relentlessly. Even today, conservative groups accuse human rights organizations of supporting or favoring the Shining Path.

Looking back, human rights activists recognize that the demands of the era — the escalation of violence — marked their trajectories more than any type of plan. These organizations emerged in a grim context of mass horror that no one could have foreseen. They had to react as the situation deteriorated and the challenges mounted. Nonetheless, they did not abandon their search for social justice, their questioning of systemic inequalities in Peru and beyond. This criticism was not the only obstacle. Human rights activists recall the challenge of tracking and disseminating information about human rights abuses, most of which were taking place in the Ayacucho countryside, an extremely dangerous area far from Lima, while also protesting Belaúnde’s austerity measures and the rolling back of the safety net created by General Velasco. The gravity of the situation forced their hand: human rights workers had to focus more of their efforts on documenting and condemning atrocities, offering legal aid, and providing sustenance in Ayacucho and other regions where the Shining Path operated. The growth of the human rights organizations also meant increased administrative work and fundraising, which demanded more and more time. The struggle for social justice had to take a back seat to the efforts to document abuses, defend the detained, and question the government’s tactics. The human rights community did count on important allies in Congress, from the left and the APRA party.

When I interviewed him in 2019, Francisco Soberón, the co-founder of APRODEH and a human rights leader until today, pointed out that the organizations continued to fight for a more just Peru, condemning opportunity gaps and the profoundly undemocratic nature of Peru. “We never pushed these issues to the side,” Soberón said. Indeed, Congressman Javier Diez Canseco (1948-2013), the founder of APRODEH, relentlessly criticized socioeconomic inequalities and capitalism. In a booklet published by APRODEH and Servicios Populares, Democracia, militarización y derechos humanos en el Perú, 1980-1984 (Democracy, Militarization, and Human Rights in Peru, 1980-1984), Diez Canseco thoroughly describes the threat to democracy in Peru posed by authoritarianism from the left and the right and the terrible economic crisis faced by the poor. Only after making these points does he begin his discussion of human rights — socioeconomic issues are not secondary.

Peruvian human rights groups did not abandon social justice issues, but understood them to be essential humanitarian priorities. The country’s extreme economic crises in the 1980s ravaged the poor and particularly the primary victims of the war: campesinos in emergency zones. Soup kitchens expanded throughout the country but could not fulfill the demand. Desplazados, the displaced, fled to cities just as unemployment surged, prices escalated, and government aid dwindled. In 1983, Lima mayor Alfonso Barrantes initiated the Vaso de Leche (Glass of Milk) program to alleviate malnutrition among children. Human rights groups in Ayacucho and throughout Peru understood their double duty of defending the detained and searching for the disappeared while also aiding their families and other victims. Disappearances and torture were not the only humanitarian tragedy in Peru at this time: poverty deepened, and many struggled to feed their families.

Under the leadership of Angélica Mendoza de Ascarza, “Mamá Angélica,” Indigenous women with disappeared family members created ANFASEP in Ayacucho in 1983. Many of these families had fled the countryside because they had been attacked or threatened, or they had left in search of information about their missing loved ones. In any case, they were forced to abandon their fields and commercial activities; they were poor and often hungry. ANFASEP almost immediately created a soup kitchen for orphans: the Comedor Popular Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, named for the Argentine Nobel laureate who visited Ayacucho in 1985. ANFASEP’s Museo de la Memoria recalls these terrible times, when women sought not only justice, but food for their families. The tens of thousands of internal refugees, who moved to Ayacucho, Lima, and other cities in the midst of one economic crisis after another in the 1980s, endured racist hostility and faced competition for any type of employment. Many desplazados could not pay bus fare and walked hundreds of miles to Lima. Mamá Angélica and other leaders of ANFASEP stressed the constant need to feed their families — they did not have the luxury to put economic issues to the side.

The economic crisis worsened after 1988 under President Alan García, and the Shining Path’s violence extended throughout much of Peru. President Alberto Fujimori threatened democracy and promoted hardline tactics, particularly after his April 1992 “self-coup.” Attuned to the nightmarish situation of human rights in Peru, the human rights communities adapted to these changes, yet the leaders never abandoned their critique of the structural causes of inequality and their search for a more just Peru. They would not recognize the supposed shift away from these questions that some in the global human rights community have decried.

Guerrillas as Perpetrators

The Peruvian human rights community collaborated with and learned from their colleagues in Chile, Argentina, and Central America, while also following the fight against apartheid in South Africa. The situation in Peru, however, diverged sharply with these other cases on one point: the guerrillas themselves were committing widespread human rights abuses. While truth commissions in Chile, Argentina, El Salvador, Guatemala, and South Africa would impute the state, the military, and the police as the perpetrators in the vast majority of cases (more than 95 percent), the Shining Path executed unarmed civilians, committed massacres, and used terrorist tactics such as car bombs in Peru. The Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) estimated that the guerrillas were the guilty party in the deaths of 54 percent of the 70,000 people killed in the conflict.

In documenting and denouncing the atrocities committed by the Shining Path, human rights organizations faced a series of challenges. Models such as those used in the heroic efforts against the military regimes in the Southern Cone focused on atrocities by the state and the military, which didn’t fit the local reality. Human rights leaders in Peru soon recognized that they had to adjust and create new parameters in order to understand and condemn the Shining Path’s methods.

Yet, information gathering — the first step in human rights work — was difficult and frustrating. The Peruvian government systematically withheld intelligence and, when probed about specific cases, would blame the Shining Path or deny the events. Journalists and activists had to piece together facts from a variety of sources and learn to deconstruct press releases for the bits of truth that emerged among the denials and misinformation. The Shining Path provided no information and instead excoriated and even attacked human right groups and journalists. Activists and journalists faced enormous obstacles in gathering basic facts.

Collecting information also proved perilous, and human rights professionals and journalists faced threats from both sides. The murder of eight journalists in Uchuraccay in 1983 revealed the dangers of reporting in Ayacucho. In 1989 and 1990, activists Coqui Huamaní, Angel Escobar, and Augusto Zuñiga were assassinated or disappeared by state agents.

Although difficult and dangerous, human rights work was also scorned. The Shining Path and the military fought a vicious war, but they agreed in their dismissal of human rights defenders. Many elected officials and even Church authorities, such as then-Bishop Juan Luis Cipriani, also chimed in with their disdain for these activists. The Shining Path, in turn, dismissed the notion of human rights as imperialist. They rejected the Geneva Convention and assassinated labor leaders such as Enrique Castilla and neighborhood activists like María Elena Moyano. The list is long.

Conservative critics vilified the human rights community for being soft on the Shining Path, for stressing the state’s “excesses” rather than those of the guerrillas. The 1970s left matured in the battles against the Morales Bermúdez regime. Did this anti-militarism and faith in revolution blind them, at least initially, to the Shining Path’s brutal authoritarianism?

The leaders I interviewed all categorically disagreed. Longtime activist Eduardo Cáceres said, “We knew the Shining Path from our years of militancy in the 1970s and understood that they were profoundly anti-democratic.” Soberón pointed out that APRODEH and other organizations had almost immediately investigated the murder of grassroots and union leaders killed or threatened by the Shining Path. They rapidly understood and feared the Shining Path and its broad definition of “the enemy.”

Early documents from APRODEH included critiques of the Shining Path. Contrary to the persistent accusations by military leaders and conservatives that human rights groups sympathized with terrorists or surreptitiously supported them — the phrase “apología del terrorismo” (apology for terrorism) has a long and dark history and remains a crime in Peru — human rights groups understood and opposed the Shining Path before almost anyone else.

The creation of the CNDDHH in 1985 marked a turning point in the human rights communities’ relationship with the Shining Path. In its founding national convention, this umbrella organization stressed its distance from the Shining Path, documenting the guerrillas’ grave responsibility for the bloodshed in Peru. Because some human rights groups and advocates had lost face when representing people who ultimately proved to be Shining Path militants, the CNDDHH limited its members’ role in defending accused Shining Path members. Human rights groups continued to fight for the rights of all prisoners to a fair trial and humane prison conditions (demands largely unmet in Peru in those years), but stipulated that the Shining Path use their own lawyers for their militants.

And yet the legal grounds for denouncing the Shining Path were unclear. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a reaction to the horrors of World War II, focused on actions by the state. Human rights organizations traditionally publicized and litigated state or para-state atrocities. Lawyers in Peru turned to international humanitarian law, particularly Article 3 of the Geneva Convention, which established the rules for humanitarian practices in international war as well as national conflicts. The fact that the Peruvian state deemed the Shining Path terrorists rather than insurgents made this international instrument more difficult to apply.

The Peruvian human rights community followed international precedent and shed the brightest light possible on illegal detentions, disappearances, massacres, and other crimes by the Peruvian state and military. They also, however, denounced crimes perpetrated by the Shining Path, particularly after the 1985 creation of the CNDDHH. At this point, they had a better understanding of the Shining Path’s authoritarian methods and counted on a national network and international support, which allowed them to gather information, including testimonies. The accusations that they were soft on the Shining Path constituted a persistent effort to counter their charges of widescale human rights abuses by the armed forces. To the contrary, Peru’s human rights community forged new trails in terms of documenting and censuring abuses perpetrated by guerrilla forces.

Legacy: The Final Report

Peru’s human rights community adapted and evolved over time. A timeline of the worst atrocities serves to summarize these changes: Uchuraccay demonstrated the dangers; numerous massacres throughout the 1980s drew attention to the brutality of both the Shining Path and the military; the 1986 extermination of prisoners in Lima contradicted President Alan García’s claims about his dedication to human rights; and the 1992 self-coup by President Alberto Fujimori brought to the fore concerns about authoritarianism and the threat to democracy, themes that would mark the entire decade. With Fujimori’s resignation in 2000, interim President Valentín Paniagua created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which included members of the CNDDHH as well as representatives of the Church and civil society.

In 2003, the commission released its nine-volume Informe Final. One of the most stunning findings of this final report was how greatly the number of dead had been miscalculated: there were not 20,000 or 30,000 casualties, as many estimated (I used these numbers in university courses at the time), but nearly 70,000. The commission’s report also updated statistics on the wounded, displaced, illegally arrested, and more.

The history of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is waiting to be written. Key members included philosopher Salomón Lerner Febres, who served as the commission’s chairman, and the anthropologist Carlos Iván Degregori. If the Informe Final can be understood as a collective work of the human rights community — with assistance from many other organizations and individuals — then it confirms the arguments made here. The report paid remarkable attention to structural inequalities and deep-rooted injustice in Peru. From page one, it underlined how Indigenous and rural people had borne the brunt of the violence. It contended that the state and civil society were slow to react because the majority of the victims were rural and Indigenous. The violence was denied or overlooked. This would not have been the case, the report contended, had the victims been urban and white. While underlining race and class hierarchies, the Truth Commission also took into consideration Peru’s severe economic crises and the suffering of the poor. It did not separate its examination of human rights abuses from socioeconomic issues and structural problems.

The Informe Final also spotlighted the violence and authoritarianism of the Shining Path. Linking them to 54 percent of the dead was one of the most cited and controversial findings, but the report went far beyond tallying numbers to explain the rise of the group from a minute Maoist splinter party. The report detailed the extension of the Shining Path into Ayacucho’s countryside, its brutal techniques, its expansion into Lima and elsewhere after 1988, and the group’s demise. This explanation reveals how good intelligence work proved far more effective than torture. The great paradox is that conservatives accuse the Truth Commission of being soft on the Shining Path, while to the contrary, it produced a multi-volume indictment of the group, deeply documented and richly argued.

The report, available online, does not limit the blame to the guerrilla groups and the armed forces. In questioning how these atrocities could have been committed, it takes a hard look at the Catholic Church, civil society, political parties, the press, and more. I have always believed that praise for the report has been muted by the breadth of its criticisms. Almost no organization escapes scrutiny in the effort to explain how tens of thousands of dead were overlooked. The report’s incorporation of socioeconomic questions, demographics, and Peru’s profound racism, as well as the document’s devastating critique of the Shining Path, reflect the merits and achievements of Peru’s human rights community. Their courage and analytical depth should not be forgotten as we reassess the work of human rights groups across the globe in recent decades. Anyone who assumes that human rights activism means foregoing issues regarding equality or turning a blind eye to insurgent atrocities should look closer at the Peruvian case.

Charles Walker is Professor of History at UC Davis, where he serves as Director of the Hemispheric Institute on the Americas. His most recent book is Witness to the Age of Revolution: The Odyssey of Juan Bautista Tupac Amaru (Oxford University Press, 2020). He spoke for CLAS in February 2020.