Fifty years after he began his work in the Delano grape-strike picket lines, Chicano theater artist and activist Luis Valdéz, brings us “The Power of Zero.” “La raza is not a race, it’s a melting pot, and everybody is welcome. We are rooted in the history of this continent. This is what we bring to the computer age — the power of zero, the power of zero to calculate, to invent, to create the universe with everybody else. We’re not any better than anybody else, but we’re just as good: we’re just as brilliant; we’re just as intelligent.”

In his lecture in celebration of the 50 years of El Teatro Campesino, founder Luis Valdéz rooted the power of zero in our bodies and across the Americas. Born in a labor camp in Delano, California, in 1940, Valdéz is regarded as the father of Chicano theater in the United States. In the 1960s, he worked alongside labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chávez in the farmworkers union strike, where he brought workers and students together to form El Teatro Campesino, a touring theater company of, by, and for the farmworkers. Valdéz was the first Chicano playwright and director to have a show on Broadway (“Zoot Suit,” 1979), and for the last 50 years, El Teatro Campesino has continued to use theater practice as a means towards the transformation of our material and spiritual realities.

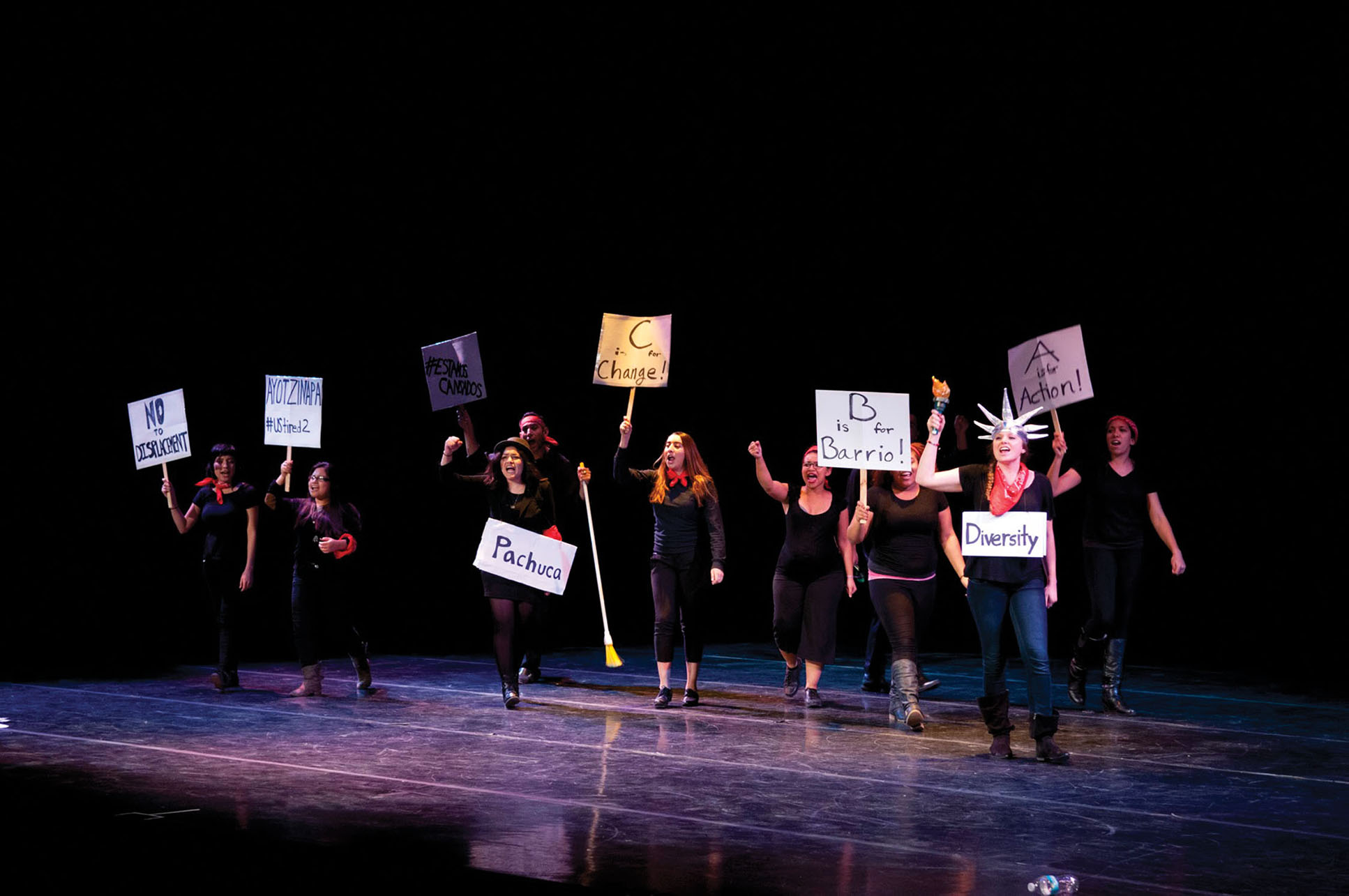

Valdéz’s continuing influence could be seen in the introductions to his lecture. Students from the Berkeley-based Teatro group opened the event with a performance that incorporated both techniques used by El Teatro Campesino and its legendary characters, the Pachuca and the Patroncito, to expose ongoing abuses of power happening on the Berkeley campus today. Following this performance, teatrera and community activist Natalie Sánchez invited the audience to think of how the arts can be used to imagine and build the future. “There can’t be a movement without movement. Listen, learn, and move. And then repeat.” With this prompt, Sánchez set the stage for Cherríe Moraga, the Chicana activist, playwright, poet, and scholar, who remarked: “I guess it takes a village to bring Luis Valdéz, huh? It’s beautiful.”

Moraga spoke of the power of Valdéz’s vision, of how for 50 years it has guided a community, the Chicano pueblo, in its flows of struggle. As a philosopher and a public intellectual, “he is someone who anticipates where we need to be politically,” Moraga said, as she acknowledged Valdéz’s leadership, tenacity, and courage. The beginnings of El Teatro Campesino render “a great model of what it is to make art practice be political practice without compromise to either of the forms.” Moraga spoke of Valdéz as an older brother, one with whom she converses and disagrees, from whom she learns as she resists and moves forward in her own practice as a Chicana artist. “In my history of watching Luis’s work I kept saying: ‘You see where that man is? I’m gonna put a woman right there in the center.’ And I thank Luis for that. Agitation, propaganda. I was pissed off. They were not true portraits of who we were; they were not, and I knew it. That’s my work right now.” In order to move forward, then, we must look at what our ancestors have done. We must “start from zero, not from scratch.”

The concept of zero played the eye of the hurricane in Valdéz’ keynote address. As he spoke of a continental America and of the genius of our pre-Columbian ancestors, zero remained the constant around which the spiral swirled. Zero is, for Valdéz, the center point through which we cross from negative to positive, the spiral through which we connect to our bodies and to each other. He develops his theory of the power of zero by unifying a continental America, finding proof of a shared world-view in the pre-Columbian linguistic roots that spread across the hemisphere. The hardy remnants of these roots are still evident in the way we use language, and we carry this ancestral knowledge in the way we speak today. “The concept of zero does not float in empty space,” Valdéz explained. “The concept of zero is embedded into our very lives.”

According to Valdéz, the concept of zero exists in four planes: body (eros), heart (pathos), mind (logos), and spirit (ethos). He uses the Maya symbol of the Hunab Ku (the square inside the circle) to articulate this theory: “I want you to imagine a circle — a pure zero circle. This is the power of the feminine. It’s continuity. It’s a matrix, but it’s a spiral. It doesn’t completely lock; it spirals. And then, within it, imagine a square — that’s the male part. This is the symbol of Hunab Ku: the square inside the circle. Hunab Ku is the creator: el único dador de la medida y el movimiento (the only giver of the measure and the movement).

Each of the four sides of the square represents one of the four planes (body, heart, mind, spirit), and each in turn consists of five steps. In the body, the power of zero lives at the base of the spine, in the solar plexus. “This is the key to movement; this is the key. And it is also the key to the Mayan zero of your body. As I say it’s a spiral — es un huracán (it’s a hurricane). You wanna see zero?” he asks, as he swirls his hips in a spiral. “It is the joy of using the zero that is inherent in your body, that frees you to be able to relate to the movement of the planet and the stars, which is why the indio dances his way to truth in ways that we don’t understand. But any culture will move in [its] own special way. Because this is universal. This is not just Chicano or Indian: it’s human. It’s human. It is the vibrant being in action.”

The zero of the heart is in developing empathy, learning to sense what other people are going through. It is the Maya precept In Lak’ech that says “you are the other me. If I love and respect you, I love and respect myself. If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself. Because we see people as others, but they’re not. I am you, and you are me, and I am my community.” This sense of the collective, of not only a continental but a universal community, is very strongly present in the third column: mind, logos, knowledge, consciousness. “There is no individual genius, there is only collective genius.” For the Maya, the word men (eagle) signifies creer, crear, ser (to believe, to create, to be), and the zero of the mind relies on our ability to create our own existence through our beliefs. “If you believe something, then you can create something. You can’t just be an artist in a vacuum, you need to believe something.” In the last column, ethics, the power of zero lies in a shared responsibility towards developing a social conscience. “You have to believe in something bigger than yourself — that’s the essence of the last column,” said Valdéz. “The world does not end here; it goes on into other people.”

Valdéz’s delivery relied on Mayan and Aztec principles to lay out the concept of zero. But passages of his own biography were central in bringing these ancient precepts closer to his audience, precisely because his theory is the result of lived experiences. “I didn’t have to go to college to learn the body was important: I was a farmworker.”

As he spoke of the importance of humility, he told the story of his very first introduction to theater. In the fall of 1946, when he was six years old, Valdéz’s family settled in a little town in the San Joaquin Valley to pick cotton. His parents enrolled him in the local school. Every day his mom would send him egg tacos for lunch in a little brown paper bag, always the same brown paper bag. There were war shortages, and a brown paper bag was a big commodity for a six-year-old migrant boy. One day after school, his brown bag disappeared, and soon enough, he discovered it had been his teacher who had taken it.

As he spoke of the importance of humility, he told the story of his very first introduction to theater. In the fall of 1946, when he was six years old, Valdéz’s family settled in a little town in the San Joaquin Valley to pick cotton. His parents enrolled him in the local school. Every day his mom would send him egg tacos for lunch in a little brown paper bag, always the same brown paper bag. There were war shortages, and a brown paper bag was a big commodity for a six-year-old migrant boy. One day after school, his brown bag disappeared, and soon enough, he discovered it had been his teacher who had taken it.

She had turned his prized paper bag into a paper-maché monkey mask for the school play. Valdéz had never heard of such a thing as a school play but was so intrigued by what his teacher told him that not only did he forgive her for taking his paper bag, but he showed up at auditions the next day. He was cast as a monkey in the school production of “Christmas in the Jungle,” his first-ever role in the theater. He made a good monkey, “a good changuito,” he said. “I got a costume that was better than my own clothes, I tell you — the mask made from mama’s taco bag.” The play was going to be his big debut before the world, and everyone — his family, neighbors, and newly made school friends — was going to see him perform. But three days before the show, he came home from school only to learn they were moving away the next day. His family had been evicted, and they had to leave the farm.

“The next morning at dawn, my dad got the truck started and pulled out. We pulled out of the camp, went through the town of Stratford where the school was, and I’ll never forget seeing this town recede into the valley fog and feeling a hole open up in my chest. I mean this could have destroyed me. This could have really done me in, as it does some kids. But I had with me the secret of paper maché, the desire to do theater, and also residual anger because we had been evicted from the labor camp. Almost 20 years later, I went to Cesar Chávez and pitched him an idea for a theater of, by, and for farmworkers.” For almost 70 years, Valdéz told his audience, he has been pouring plays and stories into that hole. “It became the hungry mouth of my creativity. A negative became a positive. How do you get from negative into positive? You have to go through zero.”

Luis Valdéz is the founder of El Teatro Campesino and an award-winning playwright and film artist. A recipient of the 2014-15 UC Regent’s Lectureship, he delivered the keynote lecture “The Power of Zero: Celebrating 50 Years of El Teatro Campesino” at UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Playhouse on Tuesday, November 18, 2014.

Martha Herrera-Lasso is a graduate student in the Department of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies at UC Berkeley.